Holley Watts

None of use really knew what we were getting into. Generally speaking,

we were educated but naïve, optimistic but cautious, determined but wary.

The challenge was then (as it still is) trying to describe it. The brochure

said it was a morale program for the able-bodied. We staffed our centers

so the men could come in and enjoy some coffee, Kool-Aid, conversation,

card games, variety shows, whatever we could organize.*

On clubmobile we went to the men in the field by helicopter, jimmy, jeep or six-by to Fire Support Bases, Landing Zones, field hospitals and base camps. We traveled in pairs, like nuns, one of us said, and used our programs to suspend their reality for just a little while.

Sometimes the word was, Charlie’s coming tonight and we’d join them to fill sandbags. As if we kept score we’d always ask,” Hi, How are ya? Where ya from?”

We were the face of the girl next door, a connection to family, community, home…and we were armed with smiles, a good ear for regional accents and a quick wit.

A friend distilled this somewhat lengthy job description—“Oh,” he said, “a cheerleader!”

Our official job title was Clubmobile Recreation Worker in the Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas program (SRAO) of the American Red Cross. Initially designed to support the morale of the troops in WWII’s European Theatre, buses were converted to mobile “canteens” for the fighting men — a place to relax with coffee, snacks, even a small library.

The Korean conflict demanded greater mobility so 2½ ton specially adapted trucks replaced the buses and hot freshly made donuts replaced the snacks. No one argued.

When the SRAO program went to Vietnam mere memories of those patriotic pastries were passed along to the next generation of troops. Heat and the helicopter killed the donut. The only survivor was the moniker “Donut Dolly” and even that took some time to arrive, coming into regular usage in the late sixties. Red Cross HQ continued to discourage its use as unprofessional and frivolous but the overriding positives of memorable alliteration and a name that evoked fun won out. The name stuck.

Not all the Donut Dollies themselves liked the term for the same reasons as the ARC HQ but wearing a sweatshirt or tee to any Vietnam veterans gathering today a neutral observer would be quick to notice that there would be a special camaraderie when to hug a complete stranger and welcome him home after all these years still makes you both cry.

It’s important to note that troop morale was always a high priority and in supportive roles women were seen as an integral part of that equation, lopsided though it was at 4,000:1 in Vietnam. Only by invitation of the military could the Red Cross girls visit troops in remote locations, field hospitals, fire support bases, landing zones and base camps. Unauthorized flights, no matter how sincere the invitation, no matter how adept the pilot, could result in immediate expulsion and a one-way ticket home at the DD’s expense.

Recently, one grunt told me he never participated in the games or even spoke to us, yet he was sure to be there whenever we visited. It was, he said, because we brought the gift of our presence, and in doing so helped save his sanity, while reminding him of his humanity. And for us, who were thousands of miles from home in a hostile environment, having left behind friends and family to serve our country by creating a touch of home in the field we simply hoped it might really count for something . . .

Women in Wartime: A Donut Dolly

by Allyson Shaw

Article from BLOG, www.vvmf.org

By Holley Watts

by Allyson Shaw

Article from BLOG, www.vvmf.org

By Holley Watts

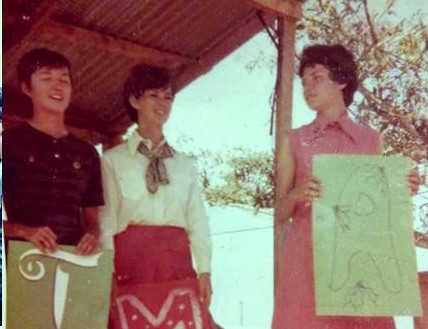

Donut Dollies in a chopper, Holly is center

Four to five decades later that “something” has counted. It’s been expressed in love, hugs, tears of gratitude, even an apology. The latter from a chopper pilot who frequently took the DDs from one stop to another before heading back home with them at the end of a very long day. “We had a lot of unpleasant odors on that aircraft but when the Donut Dollies got on board their perfume was heavenly (and us DDs regarded perfume as part of our uniform.) So why the apology? “Because,” he said, “we always took the long way home."

We traveled in pairs and made our way around a combat zone without weapons. In practice, we were a combination TV game show host / girl next door / scout den mother / Miss America / comshaw expert and sister. The GIs both wanted to talk to us and couldn’t say a thing, wanted us to stay but couldn’t get us out of their areas fast enough. We were loved, tolerated, and admired but never ignored.

It’s hard to ignore someone on a mission. Our mission was to create the diversion that would take our troops’ minds off the war, caring deeply about them, playing games and smiling, smiling, smiling.

We maintained our sanity with a sense of humor, especially initiating a new girl on her first clubmobile run. Take the term “rotor wash.” Just prior to boarding the chopper we’d introduce her to the crew then one of us would give the pilot a simple nod. His response was a “just-so” dip of the blades and the new girl’s skirt would fly straight up, usually accompanied by a scream and desperate attempts to push it back down much to the delight of the crew and other DDs (who’d quickly tucked their skirts between their knees). Welcome to ‘Nam.

The rec center was a great gathering place for conversation, card games, variety shows whatever we could organize. For

Four to five decades later that “something” has counted. It’s been expressed in love, hugs, tears of gratitude, even an apology. The latter from a chopper pilot who frequently took the DDs from one stop to another before heading back home with them at the end of a very long day. “We had a lot of unpleasant odors on that aircraft but when the Donut Dollies got on board their perfume was heavenly (and us DDs regarded perfume as part of our uniform.) So why the apology? “Because,” he said, “we always took the long way home."

We traveled in pairs and made our way around a combat zone without weapons. In practice, we were a combination TV game show host / girl next door / scout den mother / Miss America / comshaw expert and sister. The GIs both wanted to talk to us and couldn’t say a thing, wanted us to stay but couldn’t get us out of their areas fast enough. We were loved, tolerated, and admired but never ignored.

It’s hard to ignore someone on a mission. Our mission was to create the diversion that would take our troops’ minds off the war, caring deeply about them, playing games and smiling, smiling, smiling.

We maintained our sanity with a sense of humor, especially initiating a new girl on her first clubmobile run. Take the term “rotor wash.” Just prior to boarding the chopper we’d introduce her to the crew then one of us would give the pilot a simple nod. His response was a “just-so” dip of the blades and the new girl’s skirt would fly straight up, usually accompanied by a scream and desperate attempts to push it back down much to the delight of the crew and other DDs (who’d quickly tucked their skirts between their knees). Welcome to ‘Nam.

The rec center was a great gathering place for conversation, card games, variety shows whatever we could organize. For

Watching Twister

Twister we were usually able to recruit some willing Marines. The only thing they hadn’t counted on was how long we would take to spin the dial forcing them to topple over to everyone’s roars and laughter.

Before Vietnam NONE of us had experienced war. We Donut Dollies weren’t impervious to the pain of loss, but we became experts in hiding it.

I’d never forget that day in March when one of your buddies came to the center and asked me, “Do you remember John Clarke from Khe Sanh?”

He probably told me how it happened but I can’t recall his words. I remember my response, “Oh.”

I showed so little emotion I wondered later if he thought I didn’t care. Just . . . “Oh.”

I thanked him, went into the office and closed the door. I took deep breaths. I walked in circles. I stopped by one of the worktables and tried to force a chaos of papers into some logical order, but it was beyond me.

When I returned he’d already left.

I stayed busy, was chatty and that evening took home the Santa decoration John helped me make three months earlier, the one I still have.

Twister we were usually able to recruit some willing Marines. The only thing they hadn’t counted on was how long we would take to spin the dial forcing them to topple over to everyone’s roars and laughter.

Before Vietnam NONE of us had experienced war. We Donut Dollies weren’t impervious to the pain of loss, but we became experts in hiding it.

I’d never forget that day in March when one of your buddies came to the center and asked me, “Do you remember John Clarke from Khe Sanh?”

He probably told me how it happened but I can’t recall his words. I remember my response, “Oh.”

I showed so little emotion I wondered later if he thought I didn’t care. Just . . . “Oh.”

I thanked him, went into the office and closed the door. I took deep breaths. I walked in circles. I stopped by one of the worktables and tried to force a chaos of papers into some logical order, but it was beyond me.

When I returned he’d already left.

I stayed busy, was chatty and that evening took home the Santa decoration John helped me make three months earlier, the one I still have.

Angie

Angie, our unit’s pet, had several pups in the fall. We gave them away during the holidays and kept track of their whereabouts. Then in May we heard a base was overrun and among the casualties was one of our pups.

My floodgates finally broke.

We truly loved those we served, the brave and bravado, the ones that came to our centers, the ones we visited in the field and hospitals, the ones we listened to, raged at, raved about and the ones we cried for. We couldn’t have been more proud to work with and serve “America’s Best.”

In September 1967 I came back to the Real World. From the train station I caught a cab to my parents’ home, but along the way I must have been commenting a lot on how different . . . how long . . . how cool . . . how . . .

“Lady, where have you been?!” the cab driver asked. “Vietnam,”I chirped.

A quick look in his rearview mirror and he veered his cab toward the curb. I pressed hard into the back of the seat where he couldn’t reach me to throw me out. The cab stopped.

His hand flashed in one smooth slow motion—palm up on the steering column shifting into park, palm down on the meter’s arm. The meter stopped. I pressed harder into the seat. When he turned around, I braced myself.

“Welcome home, Lady . . .This ride’s on me.”

In the field there was one basic rule we learned from the men: Don’t get too close to the guys in your unit. In addition to a sense of camaraderie, the men found they could emotionally distance themselves by using nicknames, but tracking those who were either wounded or killed in an action was extremely difficult because there were no list cross-references. Fortunately, the chronologically grouped names on the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial, known as The Wall, is helpful, but matching nicknames and the individual still remains a frustration.

WHERE CAN I FIND THEM?

We volunteered to go to war, took games to the troops to make them smile

and were all the world like the girl next door with a touch of home for a little while.

To base camps, hospitals and LZs we’d float, we’d fly, we’d drive

and hoped, somehow, to remember them would keep each one alive.

War showed us no such kindness, so to honor them instead

we carved their names in granite walls to be remembered, touched, and read.

But those lists of names are useless when it’s Skeeter, Dutch, or Bro,

Four Eyes, Gramps, or Greaser, whose real names we didn’t know.

Where can I find them on The Wall? To match a name with the face we knew,

To find each one who gave their all, like Ski, Pops, Corky, Kid, or Stu.

I played Cribbage with the Cowboy and wrote letters home for Buzz,

but I can’t tell you who they were; I just know that each one was.

They introduced themselves to us as Stoney, Big Mike, Ace, and Bear.

That’s how we see and hear them still . . . just can’t find them anywhere!

Some rearranged their given names or shortened them instead.

There’s Smitty, Fox, and Bud. Yank, Mack, L.T., and Red.

They talked about their favorite things—Chip’s girl, Sly’s dawg, Buck’s car.

If we had a roll call now, I couldn’t tell you who they are.

They went by MOS and size like Gunny, Doc, and Too Tall Paul.

I’d bridge that gap and ease my pain if there were nicknames on The Wall.

It’s easy to remember Rusty, Gabby, Swede, and Jer.

They’re locked inside my memory and not going anywhere.

But I can’t reach out and touch the names that I know are on The Wall.

You see, I never got to say good-bye, or, Welcome Home, that, most of all.

There are so many stories within The Wall itself. In 1982 when The Wall was dedicated and its panels filled with over 58,000 names of our military, I found it not only a place to honor those we’d lost but also an assurance, of sorts, that someone’s absence from The Wall meant more than likely he’d survived. And in that alone, there’s hope.

Cheerleader in a war zone—a fun-sounding job with a very serious purpose. The idea of the morale program was created by Act of Congress in WWII, but it was the American Red Cross that designed the program, first in England and Europe then later in Korea where convoys of specially adapted 2½ ton trucks welcomed the incoming troop ships by producing

We volunteered to go to war, took games to the troops to make them smile

and were all the world like the girl next door with a touch of home for a little while.

To base camps, hospitals and LZs we’d float, we’d fly, we’d drive

and hoped, somehow, to remember them would keep each one alive.

War showed us no such kindness, so to honor them instead

we carved their names in granite walls to be remembered, touched, and read.

But those lists of names are useless when it’s Skeeter, Dutch, or Bro,

Four Eyes, Gramps, or Greaser, whose real names we didn’t know.

Where can I find them on The Wall? To match a name with the face we knew,

To find each one who gave their all, like Ski, Pops, Corky, Kid, or Stu.

I played Cribbage with the Cowboy and wrote letters home for Buzz,

but I can’t tell you who they were; I just know that each one was.

They introduced themselves to us as Stoney, Big Mike, Ace, and Bear.

That’s how we see and hear them still . . . just can’t find them anywhere!

Some rearranged their given names or shortened them instead.

There’s Smitty, Fox, and Bud. Yank, Mack, L.T., and Red.

They talked about their favorite things—Chip’s girl, Sly’s dawg, Buck’s car.

If we had a roll call now, I couldn’t tell you who they are.

They went by MOS and size like Gunny, Doc, and Too Tall Paul.

I’d bridge that gap and ease my pain if there were nicknames on The Wall.

It’s easy to remember Rusty, Gabby, Swede, and Jer.

They’re locked inside my memory and not going anywhere.

But I can’t reach out and touch the names that I know are on The Wall.

You see, I never got to say good-bye, or, Welcome Home, that, most of all.

There are so many stories within The Wall itself. In 1982 when The Wall was dedicated and its panels filled with over 58,000 names of our military, I found it not only a place to honor those we’d lost but also an assurance, of sorts, that someone’s absence from The Wall meant more than likely he’d survived. And in that alone, there’s hope.

Cheerleader in a war zone—a fun-sounding job with a very serious purpose. The idea of the morale program was created by Act of Congress in WWII, but it was the American Red Cross that designed the program, first in England and Europe then later in Korea where convoys of specially adapted 2½ ton trucks welcomed the incoming troop ships by producing

Holley's class of Donut Dollies, September 1966

as many as 20,000 donuts a day, proof of the axiom that an army travels on its stomach. Commonly used terms of endearment are almost always associated with food; “Sweetie Pie,” “Dumpling,” “Sugar Plum,” “Honey,” “Baby Cakes,” but it’s “Donut Dolly” that caps the list, and it’s the GI’s enthusiastic expression of appreciation that make this patriotic pastry (& the DD name) so memorable.

I left Vietnam but, truth be told, it hasn’t left me. Triggered occasionally by the most ordinary sight, sound or smell, I am instantly transported there, however briefly, and in this . . . I’m not alone.

Would I do it again? Absolutely. Would I want my daughter to go? Never.

Welcome Home!

Proud to be an American.

Proud to be a Donut Dolly!!!

* Italicized content is taken from Holley's book, Who Knew?: Reflections on Vietnam.

Allyson Shaw | March 13, 2013 at 10:46 am | Tags: American Red Cross, Donut Dolly, Holley Watts, Memories of Vietnam, Who Knew Reflections on Vietnam, women in vietnam, women in wartime, women's history month | Categories: Lessons From War | URL: http://wp.me/p10E18-qN

as many as 20,000 donuts a day, proof of the axiom that an army travels on its stomach. Commonly used terms of endearment are almost always associated with food; “Sweetie Pie,” “Dumpling,” “Sugar Plum,” “Honey,” “Baby Cakes,” but it’s “Donut Dolly” that caps the list, and it’s the GI’s enthusiastic expression of appreciation that make this patriotic pastry (& the DD name) so memorable.

I left Vietnam but, truth be told, it hasn’t left me. Triggered occasionally by the most ordinary sight, sound or smell, I am instantly transported there, however briefly, and in this . . . I’m not alone.

Would I do it again? Absolutely. Would I want my daughter to go? Never.

Welcome Home!

Proud to be an American.

Proud to be a Donut Dolly!!!

* Italicized content is taken from Holley's book, Who Knew?: Reflections on Vietnam.

Allyson Shaw | March 13, 2013 at 10:46 am | Tags: American Red Cross, Donut Dolly, Holley Watts, Memories of Vietnam, Who Knew Reflections on Vietnam, women in vietnam, women in wartime, women's history month | Categories: Lessons From War | URL: http://wp.me/p10E18-qN

Out of all the photos on this website,these are the only photos' we have of Red Cross workers.

Photos below courtesy of SGT Mike Moreno, B Co (4/69-4/70) who contacted Rene' Johnson, who was a Donut Dolly in Nam. She was with a group of doctors and nurse who came out to FSB Pershing to sing us Christmas carols - December 1969.