D-Day, June 6, 1944 - Order of Battle

12th Infantry Regiment: Colonel Russell P. Reeder, Jr

Hq Company:

1st Battalion: Lt. Colonel Charles Jackson

Hq Company:

A Company: Captain John B. Holton

B Company: Captain Irving Gray

C Company: Captain Allen H. Heidingsfelder

D Company:

2nd Battalion: Lt. Colonel Dominick Montelbano

Hq Company:

E Company: 2nd Lieutenant John T. Everett (KIA 7 June 44)

F Company: Captain Warren J. Clark

G Company:

H Company:

3rd Battalion: Lt. Colonel Thaddeus R. Dulin

Hq Company:

I Company:

K Company: Captain Kenneth R. Linder

L Company:

M Company: Captain Michael Mihalik

12th Infantry Regiment: Colonel Russell P. Reeder, Jr

Hq Company:

1st Battalion: Lt. Colonel Charles Jackson

Hq Company:

A Company: Captain John B. Holton

B Company: Captain Irving Gray

C Company: Captain Allen H. Heidingsfelder

D Company:

2nd Battalion: Lt. Colonel Dominick Montelbano

Hq Company:

E Company: 2nd Lieutenant John T. Everett (KIA 7 June 44)

F Company: Captain Warren J. Clark

G Company:

H Company:

3rd Battalion: Lt. Colonel Thaddeus R. Dulin

Hq Company:

I Company:

K Company: Captain Kenneth R. Linder

L Company:

M Company: Captain Michael Mihalik

THE 4th Infantry Division is built around three of the oldest and most distinguished infantry regiments of the United States Army. It is heir to the history of the 4th Division in World War I. Based on these traditions, we have been building a tradition of our own, one of accomplishment of assigned missions in spite of enemy, weather, fatigue or shortages of personnel or supplies. This booklet is an unfinished story. When the story is finished, may we be able to say, "We never failed."

H.W. Blakeley

Major General Commanding

THE STORY OF THE 4TH INFANTRY DIVISION

DOUBLE DEUCERS CRACK A WALL

AS lord of Europe, Hitler had boasted that American soldiers would not last nine hours if they landed in France, but --

June 6, 1944, 0630: Four companies of 8th Inf. doughs felt landing craft jar to a stop on the Normandy coast, heard ramps down with a splash, saw German pillboxes in the dunes. Then, charging through the water a long, howling line, they stormed beach defenses.

Commanded by Col. James A. Van Fleet, the 8th, with 3rd Bn., 22nd Inf., took five forts, cleared a two-mile stretch at the southeast corner of the Cherbourg peninsula within two hours. While the remainder of the division poured ashore, the 8th, 70th Tank Bn. and 4th Engineers crashed into enemy rear positions across the flooded ground behind the beach.

Col. H.A. Tribolet's 22nd Inf. swung north along the fortified coast, blasting away at forts and pillboxes of the "impregnable" Atlantic Wall. Division Artillery followed as 12th Inf., led by Col. Russell P. "Red' Reeder, pushed northwest to fill the widening gap between the 8th and 22nd.

Gen. Barton and his three brigadier generals, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., H.W. Blakeley and H.A. Barber, went ashore before 1100. Gen. Roosevelt, landing with the initial wave, won the division's first Medal of Honor.

Frantic Nazis saw the assault gain momentum. Hitler had ordered von Rundstedt and Rommel to annihilate Allied beachhead forces by nightfall. Despite heavy shelling, the division poured ashore to defy the Fuehrer's order. Not in the least "annihilated," most of the division was on French soil and had established a front four to seven miles inland as dusk fell.

Next day, the 8th broke through to the vital road center, Ste. Mere Eglise to relieve a portion of the 82nd Airborne, isolated for 36 hours by numerically superior forces. While the 12th ripped straight ahead toward Montebourg, the 22nd threw its full weight against coastal fortifications that stretched for miles.

On the third day, the 12th forged ahead boldly With both flanks exposed. Germans, fighting desperately to gain time, called on their reserve power, including two bicycle storm battalions. When the 12th hit the enemy main line of resistance near Emondeville an all-day battle, packed with repeated attacks and counter-attacks, raged. Twice, the regiment's CP was attacked, but the Nazis eventually were routed.

AS lord of Europe, Hitler had boasted that American soldiers would not last nine hours if they landed in France, but --

June 6, 1944, 0630: Four companies of 8th Inf. doughs felt landing craft jar to a stop on the Normandy coast, heard ramps down with a splash, saw German pillboxes in the dunes. Then, charging through the water a long, howling line, they stormed beach defenses.

Commanded by Col. James A. Van Fleet, the 8th, with 3rd Bn., 22nd Inf., took five forts, cleared a two-mile stretch at the southeast corner of the Cherbourg peninsula within two hours. While the remainder of the division poured ashore, the 8th, 70th Tank Bn. and 4th Engineers crashed into enemy rear positions across the flooded ground behind the beach.

Col. H.A. Tribolet's 22nd Inf. swung north along the fortified coast, blasting away at forts and pillboxes of the "impregnable" Atlantic Wall. Division Artillery followed as 12th Inf., led by Col. Russell P. "Red' Reeder, pushed northwest to fill the widening gap between the 8th and 22nd.

Gen. Barton and his three brigadier generals, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., H.W. Blakeley and H.A. Barber, went ashore before 1100. Gen. Roosevelt, landing with the initial wave, won the division's first Medal of Honor.

Frantic Nazis saw the assault gain momentum. Hitler had ordered von Rundstedt and Rommel to annihilate Allied beachhead forces by nightfall. Despite heavy shelling, the division poured ashore to defy the Fuehrer's order. Not in the least "annihilated," most of the division was on French soil and had established a front four to seven miles inland as dusk fell.

Next day, the 8th broke through to the vital road center, Ste. Mere Eglise to relieve a portion of the 82nd Airborne, isolated for 36 hours by numerically superior forces. While the 12th ripped straight ahead toward Montebourg, the 22nd threw its full weight against coastal fortifications that stretched for miles.

On the third day, the 12th forged ahead boldly With both flanks exposed. Germans, fighting desperately to gain time, called on their reserve power, including two bicycle storm battalions. When the 12th hit the enemy main line of resistance near Emondeville an all-day battle, packed with repeated attacks and counter-attacks, raged. Twice, the regiment's CP was attacked, but the Nazis eventually were routed.

Having concluded the relief of the 82nd Airborne at Ste. Mere Eglise, the 8th made a long advance to come abreast of the 12th, extending the division's line from Emondeville west to the Merderet River. The 22nd still was locked in a deadly grapple with German fortifications.

Battling all the next day, the 8th smashed the Nazi MLR near Ecausseville. Acts of gallantry and heroism were many in the vicious fighting. Co. I charged across yards of fire-swept ground; half of Co. E was cut down by ambush fire. In a final attack, 1st Bn. and Co. A, 70th Tank Bn., lifted the German line off its pivot.

While the 8th slugged through the Ecausseville line, the 12th, again ignoring its open flanks, smacked the same force it had defeated the previous day, driving the remnants to Montebourg. Meanwhile, the 22nd had buttoned up Azeville, toughest fort in the beachhead area, and shoved ahead to Chateau de Fontenay, home of Voltaire but now a Nazi strongpoint.

BY D plus four, the 22nd was pushing on to Le Theil as the 8th and 12th, hammering through desperate German defensive efforts, gained their objectives -- lines southwest and northeast of Montebourg. Here, Gen. Barton ordered them to dig in and defend their gains. A vital beachhead line secured, VII Corps now had sufficient elbow room to swing the next haymaker at the reeling Germans.

While Corps coiled to deliver the next punch, the Famous Fourth still had unfinished business. A string of forts along the coast from Crisbecq to Quineville still resisted. The rugged job of reducing them was accomplished by the Double Deucers and the 359th Inf., 9th Div., which pounded away for five days. When Quineville, last of the strongpoints, fell June 14, one of the most difficult assignments of the war was complete. The Cherbourg beachhead was firmly established in American hands.

CHERBOURG, only good port within reach of the beachhead, was a critical point. Its quick seizure was vital. As soon as troops could be landed, VII Corps cut Cherbourg off from the mainland by driving four divisions across the west coast. The drive was covered by the 4th, which held the Montebourg line. Wheeling northward, Corps, with the 4th, 9th and 79th Inf. Divs. blazing the way, seized the port.

Before daylight June 19, the 4th struck enemy forces near Montebourg. Following a barrage so close they nearly burned their faces, Joes of Co. F, 8th Inf., ripped through enemy lines to cut off the German escape route while the remainder of the regiment and the 12th herded Krauts to the "shooting gallery" Co. F had set up. Following this success, the division chased Germans 10 miles to the ring of defenses circling Cherbourg.

Battling all the next day, the 8th smashed the Nazi MLR near Ecausseville. Acts of gallantry and heroism were many in the vicious fighting. Co. I charged across yards of fire-swept ground; half of Co. E was cut down by ambush fire. In a final attack, 1st Bn. and Co. A, 70th Tank Bn., lifted the German line off its pivot.

While the 8th slugged through the Ecausseville line, the 12th, again ignoring its open flanks, smacked the same force it had defeated the previous day, driving the remnants to Montebourg. Meanwhile, the 22nd had buttoned up Azeville, toughest fort in the beachhead area, and shoved ahead to Chateau de Fontenay, home of Voltaire but now a Nazi strongpoint.

BY D plus four, the 22nd was pushing on to Le Theil as the 8th and 12th, hammering through desperate German defensive efforts, gained their objectives -- lines southwest and northeast of Montebourg. Here, Gen. Barton ordered them to dig in and defend their gains. A vital beachhead line secured, VII Corps now had sufficient elbow room to swing the next haymaker at the reeling Germans.

While Corps coiled to deliver the next punch, the Famous Fourth still had unfinished business. A string of forts along the coast from Crisbecq to Quineville still resisted. The rugged job of reducing them was accomplished by the Double Deucers and the 359th Inf., 9th Div., which pounded away for five days. When Quineville, last of the strongpoints, fell June 14, one of the most difficult assignments of the war was complete. The Cherbourg beachhead was firmly established in American hands.

CHERBOURG, only good port within reach of the beachhead, was a critical point. Its quick seizure was vital. As soon as troops could be landed, VII Corps cut Cherbourg off from the mainland by driving four divisions across the west coast. The drive was covered by the 4th, which held the Montebourg line. Wheeling northward, Corps, with the 4th, 9th and 79th Inf. Divs. blazing the way, seized the port.

Before daylight June 19, the 4th struck enemy forces near Montebourg. Following a barrage so close they nearly burned their faces, Joes of Co. F, 8th Inf., ripped through enemy lines to cut off the German escape route while the remainder of the regiment and the 12th herded Krauts to the "shooting gallery" Co. F had set up. Following this success, the division chased Germans 10 miles to the ring of defenses circling Cherbourg.

Meanwhile, the 22nd lunged forward from Le Theil in a long advance to take a hill between Cherbourg and its airport. The airfield, east of the city, was surrounded by the strongest fortifications on the peninsula. The 22nd proceeded to split the enemy force in half, then held out three days when it became surrounded. During this time, the 8th and 12th, in brilliant maneuvers and violent battles polished off enemy positions southeast of the city.

After taking Tourlaviile, Cherbourg suburb, the 12th advanced to the coast June 25. Entering Cherbourg, next day, doughs mopped up the eastern section of the city while the 9th and 79th Divs. drove in from the west and south. Exactly one week after starting the drive from Montebourg, the Famous Fourth occupied the entire city except forts along the waterfront and in the harbor.

Then the 22nd drove in on defenses surrounding the airport where 1000 Nazis fanatically fought two days before succumbing. After a long pounding by artillery, the last harbor fort surrendered, June 29. Except for the northwest corner, the Cherbourg peninsula, pivot of the invasion, was swept clean of the enemy. Preparations for the Battle of France could go into high gear. Armored divisions and heavy artillery began arriving. Air bases were moved from England to the continent. An army capable of splitting the Wehrmacht wide open was landing in France.

Fourth Division men had fought 23 days without rest, driving ahead relentlessly until victory was won. Maj. Gen. J. Lawron Collins, VII Corps Commander, in commending the division following the campaign, said:

It is a tribute to the devotion of the men of the division that severe losses in no way deterred their aggressive action. The division has been faithful to its honored dead. The 4th Infantry Division can rightly be proud of the great part that it played from the initial landing on Utah Beach to the very end of the Cherbourg campaign. I wish to express my tremendous admiration.

BREAKTHROUGH BUBBLE BURSTS

THE breakthrough was to be made on a sector south of Carentan. This meant clearing rugged terrain, full of marshes and swampy rivers -- ground ideal for defense. Germans had dug in for a permanent stay with entrenchments in every hedgerow. To reach firm ground where armored armies could operate, it was necessary to fight through that swamp country. The job was assigned to VII Corps. The 4th was in the star role.

After taking Tourlaviile, Cherbourg suburb, the 12th advanced to the coast June 25. Entering Cherbourg, next day, doughs mopped up the eastern section of the city while the 9th and 79th Divs. drove in from the west and south. Exactly one week after starting the drive from Montebourg, the Famous Fourth occupied the entire city except forts along the waterfront and in the harbor.

Then the 22nd drove in on defenses surrounding the airport where 1000 Nazis fanatically fought two days before succumbing. After a long pounding by artillery, the last harbor fort surrendered, June 29. Except for the northwest corner, the Cherbourg peninsula, pivot of the invasion, was swept clean of the enemy. Preparations for the Battle of France could go into high gear. Armored divisions and heavy artillery began arriving. Air bases were moved from England to the continent. An army capable of splitting the Wehrmacht wide open was landing in France.

Fourth Division men had fought 23 days without rest, driving ahead relentlessly until victory was won. Maj. Gen. J. Lawron Collins, VII Corps Commander, in commending the division following the campaign, said:

It is a tribute to the devotion of the men of the division that severe losses in no way deterred their aggressive action. The division has been faithful to its honored dead. The 4th Infantry Division can rightly be proud of the great part that it played from the initial landing on Utah Beach to the very end of the Cherbourg campaign. I wish to express my tremendous admiration.

BREAKTHROUGH BUBBLE BURSTS

THE breakthrough was to be made on a sector south of Carentan. This meant clearing rugged terrain, full of marshes and swampy rivers -- ground ideal for defense. Germans had dug in for a permanent stay with entrenchments in every hedgerow. To reach firm ground where armored armies could operate, it was necessary to fight through that swamp country. The job was assigned to VII Corps. The 4th was in the star role.

With only three days rest for infantrymen and none for Div Arty, the Famous Fourth -- new commanders replacing those killed or wounded -- launched its new campaign. The 8th now was commanded by Col. J.S. Rodwell, former Division Chief of Staff; the 12th by Col. J.S. Luckett; the 22nd by Col. R.T. Foster. Opposing forces were the 12th SS Panzer Div. and 6th Parachute Regt., both top-notch outfits.

For 10 days, the 4th experienced hedgerow fighting at its worst. A hundred yard gain on a 300-yard front often meant a full day's work for a battalion. Enemy lurked behind every hedgerow. German gunners were dug in every few yards. Forward movement brought certain fire. Yet 4th Joes went into this new, grim battle with the same unbeatable determination they had in storming the Atlantic Wall and capturing Cherbourg.

In a narrow bottleneck, 12th Inf. opened the attack. Second Bn. made nine separate assaults in two days, some producing space no larger than a backyard garden. When the 12th eventually ripped out the whole line, the 8th and 22nd swung into action.

On the next MLR, the 8th struggled three days before finally surrounding and annihilating an opposing regiment. On the other flank, the 22nd, now under Col. C.T. Lanham, slugged ahead against large numbers of Panther tanks proving men can beat tanks -- if they are the right men. The 22nd knocked out 20 Panthers in four days.

Germans fell back to a new defensive line along a sunken road between two swamps. When the 4th took the position after battling four days, the division was relieved and moved to the St. Lo front for its next mission.

BY mid-July, a tremendous striking force had assembled in the Allied beachhead, crowding into every field for miles around. Patton's powerful Third Army was stacked division behind division on the Cherbourg peninsula. But before this Allied might could begin crushing the Wehrmacht, the narrow limits of the beachhead had to be broken.

The plan had three essential parts: first, VII Corps would punch a hole in German lines west of St. Lo. Through this, reserves would slice westward to the coast, getting behind and destroying enemy lines and open the way for Third Army to roll. Finally, Corps would drive straight south through Villedieu and St. Pois to block out Germans while Third Army swept into open country. The Famous Fourth was to play a vital part in the first and third phases of the plan.

For 10 days, the 4th experienced hedgerow fighting at its worst. A hundred yard gain on a 300-yard front often meant a full day's work for a battalion. Enemy lurked behind every hedgerow. German gunners were dug in every few yards. Forward movement brought certain fire. Yet 4th Joes went into this new, grim battle with the same unbeatable determination they had in storming the Atlantic Wall and capturing Cherbourg.

In a narrow bottleneck, 12th Inf. opened the attack. Second Bn. made nine separate assaults in two days, some producing space no larger than a backyard garden. When the 12th eventually ripped out the whole line, the 8th and 22nd swung into action.

On the next MLR, the 8th struggled three days before finally surrounding and annihilating an opposing regiment. On the other flank, the 22nd, now under Col. C.T. Lanham, slugged ahead against large numbers of Panther tanks proving men can beat tanks -- if they are the right men. The 22nd knocked out 20 Panthers in four days.

Germans fell back to a new defensive line along a sunken road between two swamps. When the 4th took the position after battling four days, the division was relieved and moved to the St. Lo front for its next mission.

BY mid-July, a tremendous striking force had assembled in the Allied beachhead, crowding into every field for miles around. Patton's powerful Third Army was stacked division behind division on the Cherbourg peninsula. But before this Allied might could begin crushing the Wehrmacht, the narrow limits of the beachhead had to be broken.

The plan had three essential parts: first, VII Corps would punch a hole in German lines west of St. Lo. Through this, reserves would slice westward to the coast, getting behind and destroying enemy lines and open the way for Third Army to roll. Finally, Corps would drive straight south through Villedieu and St. Pois to block out Germans while Third Army swept into open country. The Famous Fourth was to play a vital part in the first and third phases of the plan.

THE roar of heavies dropping their bombs on enemy positions signalled the beginning of the drive, July 25. The 8th moved forward at 1100. Germans, stunned by the severe pounding from the air, were disorganized and broken up into isolated groups. Plunging steadily ahead, Col. Rodwell's regiment surrounded centers of resistance for later annihilation. By nightfall, a mile and a half-deep wedge had been driven into Nazi defenses with the 8th at the point and the 9th and 30th Inf. Divs. on the flanks.

Next day, as the 8th smashed ahead, the 22nd went into action with Combat Command Rose of the 2nd Armd. Div. -- a team which was to give an outstanding performance of infantry-tank coordination during the week. By noon, the Combat Command had knifed through initial defenses and several hours later was rolling southward on open roads, through St. Gilles and Canisy, reaching Mesnil Herman at dawn. Arrival of an American force at that tiny hamlet, July 27, spelled disaster for the Wehrmacht.

The 8th reached its objective, between Mesnil Herman and Marigny, the same morning. The division had achieved its breakthrough; the second phase began immediately. When the 12th whipped down to cover the westward turn of 3rd Armd. and 1st Inf. Divs., which drove for Coutances and the coast, Gen. Patton's Army was set to roll south.

The third phase centered around the bottleneck between Villedieu and Avranches through which Third Army had to pass. To guard this vital ground, VII Corps was ordered to seize a north-south line through Villedieu, St. Pois and Mortain. Double Deucers, along with CC Rose, carried out the mission July 28.

Running into strong German forces trying desperately to build a new defense line from Tessy-sur-Vire through Percy and Villedieu to Avranches, CC Rose maneuvered and fought furious battles for five days before finally buttoning up Tessy and the area near Percy.

The remainder of the 4th was on the opposite side of Percy, keeping one jump ahead of the enemy, On Aug. 1, the 12th captured Villedieu, which von Kluge repeatedly called the key to the entire operation.

NOW on the final lap, the Famous Fourth kept shoving ahead, shouldering Germans eastward into a trap forming between Third Army and the British. By Aug. 5, St. Pois and the north bank of the See River had fallen. Terrific artillery and mortar barrages mowed down routed defenders.

For this campaign, Gen. Collins again commended 4th Div., praising its "ability to take every objective assigned to it." Wrote the general:

I cannot let the division pass from my command without expressing my appreciation of the great contribution made by the 4th Infantry Division to the success of the VII Corps... The division has lived up to the high standard it set for itself in the initial campaign.

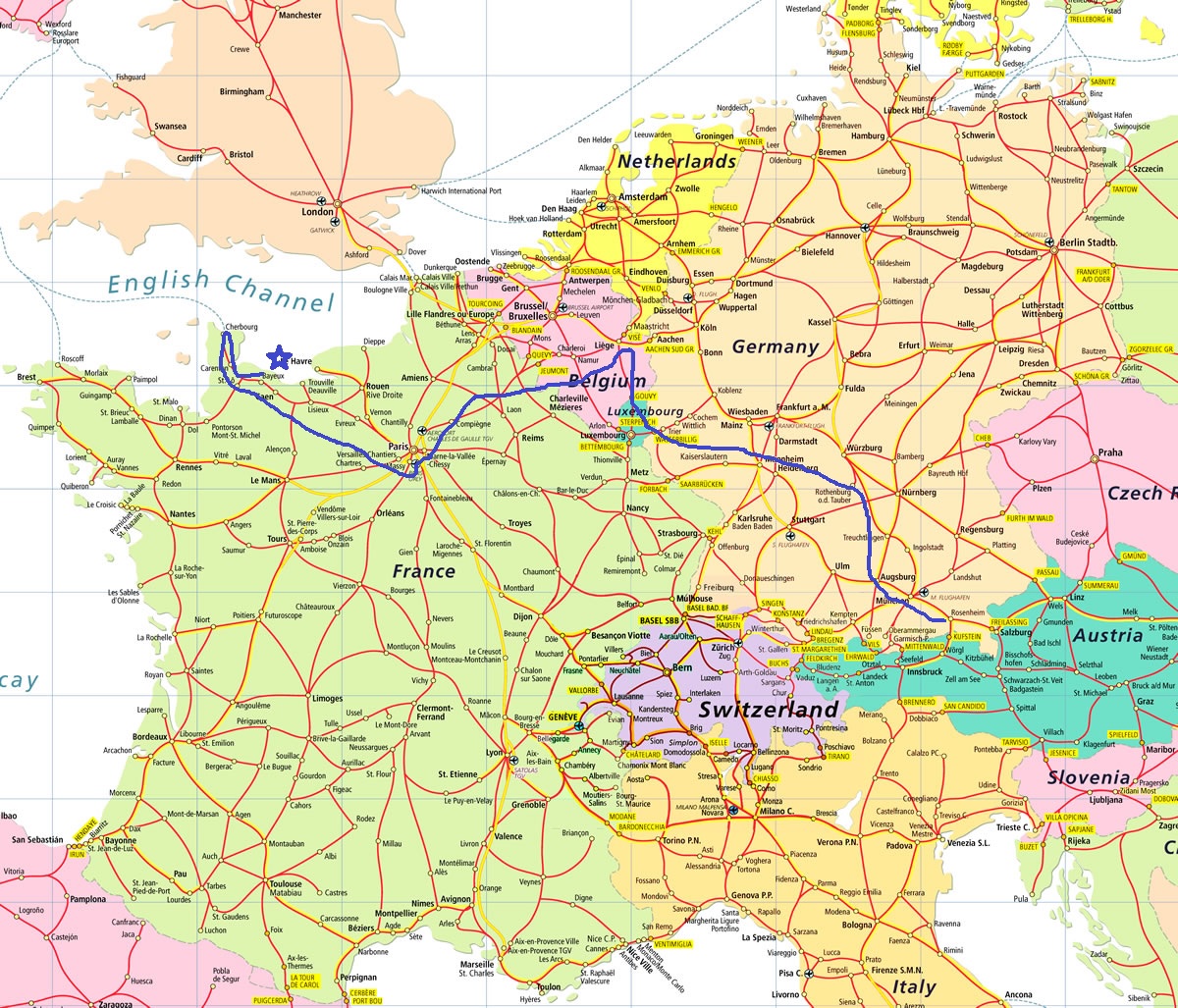

Map - Path of 4th I.D. From Utah Beach to

Paris

Next day, as the 8th smashed ahead, the 22nd went into action with Combat Command Rose of the 2nd Armd. Div. -- a team which was to give an outstanding performance of infantry-tank coordination during the week. By noon, the Combat Command had knifed through initial defenses and several hours later was rolling southward on open roads, through St. Gilles and Canisy, reaching Mesnil Herman at dawn. Arrival of an American force at that tiny hamlet, July 27, spelled disaster for the Wehrmacht.

The 8th reached its objective, between Mesnil Herman and Marigny, the same morning. The division had achieved its breakthrough; the second phase began immediately. When the 12th whipped down to cover the westward turn of 3rd Armd. and 1st Inf. Divs., which drove for Coutances and the coast, Gen. Patton's Army was set to roll south.

The third phase centered around the bottleneck between Villedieu and Avranches through which Third Army had to pass. To guard this vital ground, VII Corps was ordered to seize a north-south line through Villedieu, St. Pois and Mortain. Double Deucers, along with CC Rose, carried out the mission July 28.

Running into strong German forces trying desperately to build a new defense line from Tessy-sur-Vire through Percy and Villedieu to Avranches, CC Rose maneuvered and fought furious battles for five days before finally buttoning up Tessy and the area near Percy.

The remainder of the 4th was on the opposite side of Percy, keeping one jump ahead of the enemy, On Aug. 1, the 12th captured Villedieu, which von Kluge repeatedly called the key to the entire operation.

NOW on the final lap, the Famous Fourth kept shoving ahead, shouldering Germans eastward into a trap forming between Third Army and the British. By Aug. 5, St. Pois and the north bank of the See River had fallen. Terrific artillery and mortar barrages mowed down routed defenders.

For this campaign, Gen. Collins again commended 4th Div., praising its "ability to take every objective assigned to it." Wrote the general:

I cannot let the division pass from my command without expressing my appreciation of the great contribution made by the 4th Infantry Division to the success of the VII Corps... The division has lived up to the high standard it set for itself in the initial campaign.

Map - Path of 4th I.D. From Utah Beach to

Paris

CLINCHING THE VICTORY AT PARIS

WEARY doughs, who had rested only three days since landing two months before, now anticipated relief. But on Aug. 6, von Kluge made his desperate bid to split Allied armies by driving along the See River to Avranches. The 8th and 22nd fought fierce battles as German units penetrated their lines. Main weight of the attack fell on the 30th Div. near Mortain where three crack Panzer divisions struck. The situation became so critical by Aug. 7 that the 12th was rushed in for reinforcement.

For the next week, the 12th underwent some of the roughest combat in its history. The regiment slugged forward through artillery, mortars and screaming meemies. It was bombed by the Luftwaffe, attacked by tanks. Battalions were reduced to two or three hundred men. Joes became so tired that sheer fortitude alone kept them in the fight.

But the regiment kept pushing back the enemy. When the 12th was relieved, Aug. 12, the German counter-attack was written off as a dismal failure. The rout was on. Germans back-pedalled and didn't stop until they hit the Fatherland.

After Mortain, the 4th had its first and only real rest. No Germans were seen for 10 days; enemy artillery even moved out of range. Alerted for an urgent mission, the division was transferred to V Corps Aug. 23.

In a driving rain, the 4th rolled along the road to Paris all that night and the next day. Although the FFI had been battling Germans for several days inside the city, the capital still was surrounded. Bringing support to the patriots, the 4th and the 2nd French Armd. Div. raced to clinch the victory.

Eisenhower gave the task of taking Paris to General Omar Bradley, who chose to use French General Jacque Leclerc's Second Armored Division to make contact with the German garrison in Paris. The French Second Armored Division was a veteran unit from the North African campaign, and most importantly politically, French in ethnicity. The American Fourth Division was also dispatched to assist, together with a British contingent.

Against Adolf Hitler's specific orders, von Choltitz chose not to fight for Paris. He began evacuating the city in secret before the Allies arrived, as observed by Allied intelligence. On 23 Aug, elements of the US Army 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron rode ahead of French tanks, and reached the outskirts of Paris by the evening of 24 Aug. Noting that the light German resistance had been eliminated, the cavalry made way for the French troops, which entered the city at dawn of 25 Aug. Just behind them were American troops from the 12th Infantry Regiment, which arrived at Notre Dame by 0830. By 1530, Allied troops were gathered at the Arc de Triomphe. The official unit history of the US Army 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, which entered the city ahead of the 12th Infantry Regiment, noted that the men "received uninhibited and enthusiastic greetings of the Parisienes and Parisiennes,... Morale was never higher."

The 4th bivouacked 12 miles south of the city as Germans retreated hastily across the Seine River. The 22nd set out in pursuit. That evening, 2nd French Armd. met strong opposition between Versailles and Paris. At midnight, the 12th was ordered to move into the city.

EARLY Aug. 25, while the 8th and 22nd crossed the Seine, the 12th advanced north on Boulevard d'Orleans, ready to take on all comers. For once, doughs found the job nearly accomplished before they arrived. On trucks, the 12th rode in triumphal procession through streets jammed from wall to wall with thousands of joyous Parisians. Third Bn. reached Notre Dame Cathedral at high noon, first Allied military unit to see the famous square for more than four years. Other battalion elements arrived as fast as they could push their way through the surging throng.

Paris was free -- the biggest news the world had heard since D-Day. Gen. Barton and Gen. Blakeley represented the division when the German commander surrendered at the Gare de Montparnasse.

Moving to the north suburbs of Paris, the division cleared the city. Germans now were frantically trying to get out of France. Next, the Famous Fourth advanced northeast as First Army's drive to the Belgian border picked up speed.

TWENTY-SIX years earlier, a new and not yet famous 4th Div. had advanced northeast from Paris, The forward movement ended at Meaux after heavy fighting. The Ivy Division had entered its first battle along the Ourcq River where a week of bitter battling produced a gain of only five square miles.

The Famous Fourth roared along the banks of the same river, sweeping German rear guards from hundreds of square miles each day. Passing the Foret de Compiegne where the armistice was signed in 1918, the division bridged the Aisne River in one afternoon, then raced through territory which Germans had held against all attacks in World War I.

Double Deucers, riding hellbent for election, passed Soissons and Laon, swept through Crecy, Guise and Le Cateau. In two days they reached Landrecies, close to the border. On a broad front squarely across enemy escape routes, the 8th and 12th occupied the area near St. Quentin.

Two days later, V Corps rushed eastward to the Meuse River, crossing it before reeling Germans could take advantage of excellent natural defenses. In the same sector where the Nazis had routed the French in 1940, V Corps now surprised the Germans by spanning the Meuse and driving on the Fatherland.

For the next week, the 4th notched back the throttle as it pounded through Belgium, fighting German rear guards and liberating hundreds of towns. St. Hubert, La Roche, Houffalize, Bastogne, St. Vith fell before the division's surging drive. Everywhere, home-made Allied flags appeared on houses.

At 2120, Sept. 11, 4th Div. patrols crossed the German border to be followed next day by the entire 22nd Inf. First proclamation of Allied Military Government was posted at Elcherat, Germany. "Sacred" Germany, safe from invasion since Napoleon's day, now was about to get the works.

Paris was free -- the biggest news the world had heard since D-Day. Gen. Barton and Gen. Blakeley represented the division when the German commander surrendered at the Gare de Montparnasse.

Moving to the north suburbs of Paris, the division cleared the city. Germans now were frantically trying to get out of France. Next, the Famous Fourth advanced northeast as First Army's drive to the Belgian border picked up speed.

TWENTY-SIX years earlier, a new and not yet famous 4th Div. had advanced northeast from Paris, The forward movement ended at Meaux after heavy fighting. The Ivy Division had entered its first battle along the Ourcq River where a week of bitter battling produced a gain of only five square miles.

The Famous Fourth roared along the banks of the same river, sweeping German rear guards from hundreds of square miles each day. Passing the Foret de Compiegne where the armistice was signed in 1918, the division bridged the Aisne River in one afternoon, then raced through territory which Germans had held against all attacks in World War I.

Double Deucers, riding hellbent for election, passed Soissons and Laon, swept through Crecy, Guise and Le Cateau. In two days they reached Landrecies, close to the border. On a broad front squarely across enemy escape routes, the 8th and 12th occupied the area near St. Quentin.

Two days later, V Corps rushed eastward to the Meuse River, crossing it before reeling Germans could take advantage of excellent natural defenses. In the same sector where the Nazis had routed the French in 1940, V Corps now surprised the Germans by spanning the Meuse and driving on the Fatherland.

For the next week, the 4th notched back the throttle as it pounded through Belgium, fighting German rear guards and liberating hundreds of towns. St. Hubert, La Roche, Houffalize, Bastogne, St. Vith fell before the division's surging drive. Everywhere, home-made Allied flags appeared on houses.

At 2120, Sept. 11, 4th Div. patrols crossed the German border to be followed next day by the entire 22nd Inf. First proclamation of Allied Military Government was posted at Elcherat, Germany. "Sacred" Germany, safe from invasion since Napoleon's day, now was about to get the works.

D-DAY: READY AND RARING TO GO

HITLER boasted that his vaunted West Wall was impregnable. The 4th set out to prove him a liar. Where the division assaulted the barrier, east of St. Vith, strong defenses were built on a steep, thickly wooded ridge -- the Schnee Eifel.

When the 12th and 22nd climbed this Sept. 14, the enemy still was disorganized from his headlong retreat. Both regiments overran pillboxes, broke through to the top of the ridge, fanning out behind the Siegfried Line.

Germans made a desperate stand. They rushed in reinforcements as the 12th and 22nd split in a twin-pronged drive. When Germans filtered into the 4th's position from behind, the 8th was recalled from an advance farther north to fill the center gap.

The division front, now extended 15 miles, prevented further penetration without support, so the 4th was ordered to halt, dig in. After 15 weeks of continual advance, the Double Deucers settled down to hold a stabilized line. After guarding the Schnee Eifel and later the Monschau front, the 4th moved to Hurtgen Forest Nov. 5.

Of the campaign just finished, Lt. Gen. (then Maj. Gen.) L.T. Gerow, V Corps Commander wrote:

The aggressive courage, unselfish devotion, tenacity of purpose and outstanding leadership of all ranks is evidenced by the fact that the 4th Infantry Division has never failed to capture its assigned objectives and has never lost ground to the enemy... It is without reservation that I say you have a hard fighting, smooth functioning division.

FOR the second time, the 4th Div. had driven Germans from France and Belgium. In 1918, the Ivy Division, comprising the 39th, 47th, 58th and 59th Inf. Regts., the 13th, 16th and 77th FA Regts., and the 4th Engrs., also fought Germans in Franuce.

The old 4th, created Dec. 3, 1917, at Camp Greene, N.C., set a remarkable record. It organized, trained, crossed the Atlantic and fought in four offensives before the armistice was signed. It saw heavy action in the Aisne-Mare offensive, on the Vesle, at St. Mihiel and in the Meuse-Argonne before occupying Germany for seven months.

HITLER boasted that his vaunted West Wall was impregnable. The 4th set out to prove him a liar. Where the division assaulted the barrier, east of St. Vith, strong defenses were built on a steep, thickly wooded ridge -- the Schnee Eifel.

When the 12th and 22nd climbed this Sept. 14, the enemy still was disorganized from his headlong retreat. Both regiments overran pillboxes, broke through to the top of the ridge, fanning out behind the Siegfried Line.

Germans made a desperate stand. They rushed in reinforcements as the 12th and 22nd split in a twin-pronged drive. When Germans filtered into the 4th's position from behind, the 8th was recalled from an advance farther north to fill the center gap.

The division front, now extended 15 miles, prevented further penetration without support, so the 4th was ordered to halt, dig in. After 15 weeks of continual advance, the Double Deucers settled down to hold a stabilized line. After guarding the Schnee Eifel and later the Monschau front, the 4th moved to Hurtgen Forest Nov. 5.

Of the campaign just finished, Lt. Gen. (then Maj. Gen.) L.T. Gerow, V Corps Commander wrote:

The aggressive courage, unselfish devotion, tenacity of purpose and outstanding leadership of all ranks is evidenced by the fact that the 4th Infantry Division has never failed to capture its assigned objectives and has never lost ground to the enemy... It is without reservation that I say you have a hard fighting, smooth functioning division.

FOR the second time, the 4th Div. had driven Germans from France and Belgium. In 1918, the Ivy Division, comprising the 39th, 47th, 58th and 59th Inf. Regts., the 13th, 16th and 77th FA Regts., and the 4th Engrs., also fought Germans in Franuce.

The old 4th, created Dec. 3, 1917, at Camp Greene, N.C., set a remarkable record. It organized, trained, crossed the Atlantic and fought in four offensives before the armistice was signed. It saw heavy action in the Aisne-Mare offensive, on the Vesle, at St. Mihiel and in the Meuse-Argonne before occupying Germany for seven months.

June, 1940, when it seemed that no power on earth could stand against the Wehrmacht, the new 4th was activated. It was organized at Ft. Benning, Ga., with the 8th, 22nd and 29th Inf. Regts.; the 20th, 29th, 42nd and 44th FA Bns; the 4th Engr. Bn., and 4th Special Troops. Later, 12th Inf. replaced 29th Inf. After training at Ft. Benning, maneuvering in Louisiana and Carolina, the 4th served as the War Department's guinea pig in experiments with motorized divisions.

Gen. R.O. Barton, first Chief of Staff, returned as Division Commander in June, 1942. Under Gen. Barton's leadership, the 4th shaped up rapidly as a hard-hitting unit.

AFTER packing up for the North African invasion in Sept. 1942, the 4th was squeezed out by shipping shortages. For the next six months, it set a record as the most frequently alerted unit in the Army. While the fighting raged in Africa and Sicily and landings were made in Italy, the division went on training at Camp Gordon, Ga. and Ft. Dix, N.J., waiting impatiently for its chance.

In Autumn, 1943, the 4th became a straight infantry division, taking its amphibious training at Camp Gordon Johnston, Fla. After two years of restless waiting, the division sailed for England, Jan. 18, 1944. At "Sunny Devon," Joes rehearsed Normandy landings time and time again on the beach at Slapton Sands. D-Day found the 4th ready and raring to go.

HURTGEN -- "DEATH FACTORY"

HURTGEN WAS a cold, jungle hell -- a death factory. Blocking approaches to Cologne and the Ruhr, Hurtgen was a "must" objective. The terrain was difficult enough -- steep hills, thick woods, numerous creeks, poor roads. Across the front stretched belts of mines and barbed wire rigged with booby traps. Dug-in machine guns were set up to spray the entire area with interlocking fire.

Artillery, doubly dangerous in the woods because of tree bursts, was zeroed in on every conceivable objective. Weather was pure misery -- constant rain, snow, near freezing temperatures. Living for days in water-filled holes, usually without blankets, troops had no escape from cold and wet.

Before the main offensive gut underway, the 12th rushed south to aid a division under heavy enemy pressure. The regiment fought bitterly for eight days, attacking and counter-attacking without flank support. Although it suffered heavy casualties, the 12th returned to join the division's assault Nov. 16.

Gen. R.O. Barton, first Chief of Staff, returned as Division Commander in June, 1942. Under Gen. Barton's leadership, the 4th shaped up rapidly as a hard-hitting unit.

AFTER packing up for the North African invasion in Sept. 1942, the 4th was squeezed out by shipping shortages. For the next six months, it set a record as the most frequently alerted unit in the Army. While the fighting raged in Africa and Sicily and landings were made in Italy, the division went on training at Camp Gordon, Ga. and Ft. Dix, N.J., waiting impatiently for its chance.

In Autumn, 1943, the 4th became a straight infantry division, taking its amphibious training at Camp Gordon Johnston, Fla. After two years of restless waiting, the division sailed for England, Jan. 18, 1944. At "Sunny Devon," Joes rehearsed Normandy landings time and time again on the beach at Slapton Sands. D-Day found the 4th ready and raring to go.

HURTGEN -- "DEATH FACTORY"

HURTGEN WAS a cold, jungle hell -- a death factory. Blocking approaches to Cologne and the Ruhr, Hurtgen was a "must" objective. The terrain was difficult enough -- steep hills, thick woods, numerous creeks, poor roads. Across the front stretched belts of mines and barbed wire rigged with booby traps. Dug-in machine guns were set up to spray the entire area with interlocking fire.

Artillery, doubly dangerous in the woods because of tree bursts, was zeroed in on every conceivable objective. Weather was pure misery -- constant rain, snow, near freezing temperatures. Living for days in water-filled holes, usually without blankets, troops had no escape from cold and wet.

Before the main offensive gut underway, the 12th rushed south to aid a division under heavy enemy pressure. The regiment fought bitterly for eight days, attacking and counter-attacking without flank support. Although it suffered heavy casualties, the 12th returned to join the division's assault Nov. 16.

On the south flank of the offensive, the 4th attacked through the forest toward Duren. Again, its front was extended. To the left of the 12th, now commanded by Col. R.H. Chance, was the 22nd and the 8th, the latter now led by Col. R.G. McKee. For three days the regiment struggled to crack the first enemy lines.

Every yard was difficult, dangerous. Firebreaks and clearings were mined. In the thick woods, German positions couldn't be detected more than five yards away. Yet, Nazi outposts could observe the 4th's approach. Every move brought instant artillery and mortar fire.

The line of wire and mines seemed impossible to crack. Machine guns and artillery blunted every attack. Reaching a firebreak which crossed the front, the 70th Tank Bn. finally broke the wire, rolled beyond. Infantry followed in tracks made by tanks after armor had detonated anti-personnel mines.

In pushing the front forward 1000 yards, the division suffered heavy casualties the first five days. The next enemy line was as tough as the first. The identical procedure had to be repeated.

Another five days produced another destroyed line, another mile gained. Germans brought up fresh regiments, counter-attacking daily. Often, companies were caught before they had a chance to get set. It took another battle to throw back stubborn Germans. After every advance, men spent hours digging holes and cutting logs to cover them. Artillery often whined, burst in the trees before shelters could be finished.

After a day and night of vicious fighting, the 22nd reached Grosshau Nov. 27, wiping out German defenders before going on to the last strip of the forest beyond the town. Still in the woods, the 8th and 12th crashed the third MLR, which was as rough as the others. The Nazis had overlooked no bet. Every approach was covered with every device of defensive warfare. Neither skill nor genius could find an easy way. It took sheer guts to win.

After three days, both regiments shattered the last line and broke through near the east edge of the forest. Then came welcome news. Relief! The 22nd moved to Luxembourg Dec. 3, followed by the 12th four days later and the 8th on Dec. 13.

Gen. Collins again paid tribute to the Famous Fourth:

Every yard was difficult, dangerous. Firebreaks and clearings were mined. In the thick woods, German positions couldn't be detected more than five yards away. Yet, Nazi outposts could observe the 4th's approach. Every move brought instant artillery and mortar fire.

The line of wire and mines seemed impossible to crack. Machine guns and artillery blunted every attack. Reaching a firebreak which crossed the front, the 70th Tank Bn. finally broke the wire, rolled beyond. Infantry followed in tracks made by tanks after armor had detonated anti-personnel mines.

In pushing the front forward 1000 yards, the division suffered heavy casualties the first five days. The next enemy line was as tough as the first. The identical procedure had to be repeated.

Another five days produced another destroyed line, another mile gained. Germans brought up fresh regiments, counter-attacking daily. Often, companies were caught before they had a chance to get set. It took another battle to throw back stubborn Germans. After every advance, men spent hours digging holes and cutting logs to cover them. Artillery often whined, burst in the trees before shelters could be finished.

After a day and night of vicious fighting, the 22nd reached Grosshau Nov. 27, wiping out German defenders before going on to the last strip of the forest beyond the town. Still in the woods, the 8th and 12th crashed the third MLR, which was as rough as the others. The Nazis had overlooked no bet. Every approach was covered with every device of defensive warfare. Neither skill nor genius could find an easy way. It took sheer guts to win.

After three days, both regiments shattered the last line and broke through near the east edge of the forest. Then came welcome news. Relief! The 22nd moved to Luxembourg Dec. 3, followed by the 12th four days later and the 8th on Dec. 13.

Gen. Collins again paid tribute to the Famous Fourth:

The drive required a continuous display of top-notch leadership and the highest order of individual courage under the most adverse conditions. The fact that the 4th Division overcame these many difficulties and drove the enemy from the dominating hills overlooking the Roer River is a tribute to the skill, determination and aggressiveness of all ranks.

AFTER Hurtgen, Luxembourg was heaven. Dry, warm houses were a welcome change from holes full of icy water, from incessant shellings. Since the division's sector extended 35 miles, each platoon covered about a mile. Although there was snow, rain and cold for men on post, it was a comparative rest.

FAMOUS FOURTH LOOKS AHEAD

IT will be easy to take Dickweiler," the German battalion commander told his men. "It is held by only two platoons."

He was right about the two platoons. The Fourth Infantry Division was widely dispersed along a 35-mile front in Luxembourg -- a depleted company every two miles or more. But the Germans didn't take Dickweiler. They were slashed to ribbons trying.

This procedure was duplicated everywhere the German 212th Div. smacked the 12th Inf. Regt. Enemy forces swarmed around small units, outnumbering them as much as five to one. But the 12th doughs fought on doggedly holding each isolated town until reinforcements came.

At Echternach and other places when reinforcements didn't get through, the 12th held anyway. Without these towns, the Germans couldn't use the roads. Without these roads, the Nazi drive for Luxembourg City was doomed to failure.

BUT it didn't last. Germans crossed the river at dawn Dec. 16, attacking the 12th and hitting division outposts from all directions. American platoons battled German battalions. Some platoons, struck from the rear, were overcome. Others withdrew, fighting their way to company areas.

That morning, Gen. Barton issued an order: "There will be no retrograde movement in this sector."

The 4th would stand and fight it out!

When a German battalion swooped down on Berdorf, lone defenders comprised a company headquarters, one rifle squad, two anti-tank squads and a four-man mortar squad. The make-shift defense took refuge in the Parc Hotel, a rifle in every other window, and withstood repeated attacks. Pulverizing German artillery blasted off the roof and part of the hotel's third floor. Doughs moved to other windows, kept firing.

Two platoons were at Dickweiler, three at Osweiler. Units in both towns were surrounded by full strength battalions. Every time Germans attacked, Joes waited until they closed in, then sprayed the Nazis with a withering fire that stopped succeeding assaults with heavy losses.

Other German units, by-passing the two towns, ran into the 12th's reserves. Companies, with a few tanks as support, boldly moved forward to take on a complete battalion. The Americans disregard for the odds confused and worried the Germans. This thin-spread outfit was supposed to be easy pickings. Instead, it was giving the Nazis a terrific headache.

Transferred from their own thinly defended sectors, battalions of the 8th and 22nd came up the next morning to plunge into action. A fresh German regiment attempted a flanking move through a valley at the sector's edge, but the 4th Engr. Bn. and the 4th Recon Troop repulsed the attack.

AFTER Hurtgen, Luxembourg was heaven. Dry, warm houses were a welcome change from holes full of icy water, from incessant shellings. Since the division's sector extended 35 miles, each platoon covered about a mile. Although there was snow, rain and cold for men on post, it was a comparative rest.

FAMOUS FOURTH LOOKS AHEAD

IT will be easy to take Dickweiler," the German battalion commander told his men. "It is held by only two platoons."

He was right about the two platoons. The Fourth Infantry Division was widely dispersed along a 35-mile front in Luxembourg -- a depleted company every two miles or more. But the Germans didn't take Dickweiler. They were slashed to ribbons trying.

This procedure was duplicated everywhere the German 212th Div. smacked the 12th Inf. Regt. Enemy forces swarmed around small units, outnumbering them as much as five to one. But the 12th doughs fought on doggedly holding each isolated town until reinforcements came.

At Echternach and other places when reinforcements didn't get through, the 12th held anyway. Without these towns, the Germans couldn't use the roads. Without these roads, the Nazi drive for Luxembourg City was doomed to failure.

BUT it didn't last. Germans crossed the river at dawn Dec. 16, attacking the 12th and hitting division outposts from all directions. American platoons battled German battalions. Some platoons, struck from the rear, were overcome. Others withdrew, fighting their way to company areas.

That morning, Gen. Barton issued an order: "There will be no retrograde movement in this sector."

The 4th would stand and fight it out!

When a German battalion swooped down on Berdorf, lone defenders comprised a company headquarters, one rifle squad, two anti-tank squads and a four-man mortar squad. The make-shift defense took refuge in the Parc Hotel, a rifle in every other window, and withstood repeated attacks. Pulverizing German artillery blasted off the roof and part of the hotel's third floor. Doughs moved to other windows, kept firing.

Two platoons were at Dickweiler, three at Osweiler. Units in both towns were surrounded by full strength battalions. Every time Germans attacked, Joes waited until they closed in, then sprayed the Nazis with a withering fire that stopped succeeding assaults with heavy losses.

Other German units, by-passing the two towns, ran into the 12th's reserves. Companies, with a few tanks as support, boldly moved forward to take on a complete battalion. The Americans disregard for the odds confused and worried the Germans. This thin-spread outfit was supposed to be easy pickings. Instead, it was giving the Nazis a terrific headache.

Transferred from their own thinly defended sectors, battalions of the 8th and 22nd came up the next morning to plunge into action. A fresh German regiment attempted a flanking move through a valley at the sector's edge, but the 4th Engr. Bn. and the 4th Recon Troop repulsed the attack.

Moving through the undefended woods at the center of the division's lines, the German 316th Regt. shoved all the way to the rear areas, surrounding a battalion CP. Although the 12th's Cannon Co. was caught with its guns coupled up, Krauts got the bigger surprise. Cannoneers loaded guns and fired point blank while the remainder of the company blazed away with carbines.

A second CP was surrounded when Nazis attacked 2nd Bn., 22nd Inf. Grabbing artillerymen to serve as infantry, Co. C, 70th Tank Bn., relieved the handful of Joes staving off the assault. This was the straw that broke the German breakthrough attempts, but still the enemy wasn't finished.

Withdrawing to their original starting positions, Nazis stormed Berdorf and Echternach. After completely encircling Echternach, the enemy recaptured the town. By now, the 4th had no reserves to call upon. Cooks, quartermasters, MPs -- every possible man in the division -- was in the line.

Gen. Barton decided to pull out of Berdorf and Lauterborn and withdraw to a solid MLR. Garrisons that had held against all odds fell back to the next line.

Germans followed. But they were too late. After attacking monotonously for three days, three battalions of the German 212th Div., already badly mauled, were wiped out. Only one German of 2nd Bn., 316th, survived the battle at Michelshof. He surrendered.

TRANSFERRED from the division Dec. 27, Gen. Barton had commanded the Famous Fourth for two and a half years, leading it with brilliant success through nine operations. Succeeding him was Brig. Gen. Harold W. Blakeley, artillery commander. Taking over Gen. Blakeley's post was Col. R.T. Guthrie.

Under Gen. Blakeley, the battle of Luxembourg was pushed to complete victory. Along with the 5th Inf. Div., which took over a portion of the front, Double Deucers seized the offensive. Germans failed to hold the little territory they had recaptured. By Jan. 1, remnants of the 212th Div. reeled backward.

Von Rundstedt's big gamble was definitely washed up by mid-January; the bulge was whittled down all along the line. The 4th now was sent in to cut off another chunk.

At 0300 Jan. 18, the 8th crossed the Sauer River in the winter's roughest weather. A strong north wind lashed stinging rain, sleet and snow in doughs' faces. Trucks and trailers skidded and ditched along steep, ice-covered roads. The bridging job was the toughest 4th Engrs. ever had experienced.

A second CP was surrounded when Nazis attacked 2nd Bn., 22nd Inf. Grabbing artillerymen to serve as infantry, Co. C, 70th Tank Bn., relieved the handful of Joes staving off the assault. This was the straw that broke the German breakthrough attempts, but still the enemy wasn't finished.

Withdrawing to their original starting positions, Nazis stormed Berdorf and Echternach. After completely encircling Echternach, the enemy recaptured the town. By now, the 4th had no reserves to call upon. Cooks, quartermasters, MPs -- every possible man in the division -- was in the line.

Gen. Barton decided to pull out of Berdorf and Lauterborn and withdraw to a solid MLR. Garrisons that had held against all odds fell back to the next line.

Germans followed. But they were too late. After attacking monotonously for three days, three battalions of the German 212th Div., already badly mauled, were wiped out. Only one German of 2nd Bn., 316th, survived the battle at Michelshof. He surrendered.

TRANSFERRED from the division Dec. 27, Gen. Barton had commanded the Famous Fourth for two and a half years, leading it with brilliant success through nine operations. Succeeding him was Brig. Gen. Harold W. Blakeley, artillery commander. Taking over Gen. Blakeley's post was Col. R.T. Guthrie.

Under Gen. Blakeley, the battle of Luxembourg was pushed to complete victory. Along with the 5th Inf. Div., which took over a portion of the front, Double Deucers seized the offensive. Germans failed to hold the little territory they had recaptured. By Jan. 1, remnants of the 212th Div. reeled backward.

Von Rundstedt's big gamble was definitely washed up by mid-January; the bulge was whittled down all along the line. The 4th now was sent in to cut off another chunk.

At 0300 Jan. 18, the 8th crossed the Sauer River in the winter's roughest weather. A strong north wind lashed stinging rain, sleet and snow in doughs' faces. Trucks and trailers skidded and ditched along steep, ice-covered roads. The bridging job was the toughest 4th Engrs. ever had experienced.

Surprised by the first assault, Germans were quick to retaliate. Advancing northward across the front of the Siegfried Line, the 8th took heavy flanking fire from hillside defenders. Doggedly, 8th doughs pushed on to their objective. Farther north, the 12th overran Fuhren and took the high ground near Vianden. By Jan. 21, the division had captured all its objectives.

In commending the 4th, Maj. Gen. M.S. Eddy, XII Corps Commander, said:

Your combat record since D-Day has been in the highest traditions of the American Army... Your execution of this mission (clearing the enemy from positions west of the Our River) was a demonstration of sound tactical planning and bold courage by a division who knew its business. Let me express my deep appreciation of your magnificent contribution to the successful operation of the XII Corps in Luxembourg.

Five days later, the Famous Fourth moved again, joining in the pursuit of Germans, now in headlong retreat from Belgium. Crossing the border in the same place it had back in September, the division recaptured familiar villages. Elcherat, Winterscheid, Bleialf were among those falling to the 12th.

Scaling the Schnee Eifel in a snow storm, the 8th closed. in on pillboxes and entrenchments from the rear to recover in two days all that segment of the Siegfried Line which it had won in September. The 22nd took the fortified town of Brandscheid, which previously had withstood all attacks.

DOUBLE Deucers drove through snow, rain, and mud, deeper and deeper into the Rhineland. Germans fought and fell back from village to village; nowhere did they stand more than a day. On Feb. 9, the 8th crossed the Prum River. Two days later, the 22nd took Prum.

Pausing long enough for other divisions to draw abreast, the 4th, along with the 11th Armd. Div., pushed on to cross the Kyll River at the beginning of March.

A task force under Brig. Gen. Rodwell made a dramatic 24-hour dash which carried it more than 20 miles, capturing Adenau and Reifferscheid.

The division took added pride in turning Adenau over to Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, VII Corps Commander. Gen Middleton was an officer in the old 4th which had occupied the town 27 years earlier.

As Gen. Rodwell's force was fighting forward, orders arrived to move the division 200 miles south, to Gen. Patch's Seventh Army. New problems, new battles await the 4th, but it faces them with calm, certain confidence that it will do what it always has done -- accomplish its mission.

In commending the 4th, Maj. Gen. M.S. Eddy, XII Corps Commander, said:

Your combat record since D-Day has been in the highest traditions of the American Army... Your execution of this mission (clearing the enemy from positions west of the Our River) was a demonstration of sound tactical planning and bold courage by a division who knew its business. Let me express my deep appreciation of your magnificent contribution to the successful operation of the XII Corps in Luxembourg.

Five days later, the Famous Fourth moved again, joining in the pursuit of Germans, now in headlong retreat from Belgium. Crossing the border in the same place it had back in September, the division recaptured familiar villages. Elcherat, Winterscheid, Bleialf were among those falling to the 12th.

Scaling the Schnee Eifel in a snow storm, the 8th closed. in on pillboxes and entrenchments from the rear to recover in two days all that segment of the Siegfried Line which it had won in September. The 22nd took the fortified town of Brandscheid, which previously had withstood all attacks.

DOUBLE Deucers drove through snow, rain, and mud, deeper and deeper into the Rhineland. Germans fought and fell back from village to village; nowhere did they stand more than a day. On Feb. 9, the 8th crossed the Prum River. Two days later, the 22nd took Prum.

Pausing long enough for other divisions to draw abreast, the 4th, along with the 11th Armd. Div., pushed on to cross the Kyll River at the beginning of March.

A task force under Brig. Gen. Rodwell made a dramatic 24-hour dash which carried it more than 20 miles, capturing Adenau and Reifferscheid.

The division took added pride in turning Adenau over to Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, VII Corps Commander. Gen Middleton was an officer in the old 4th which had occupied the town 27 years earlier.

As Gen. Rodwell's force was fighting forward, orders arrived to move the division 200 miles south, to Gen. Patch's Seventh Army. New problems, new battles await the 4th, but it faces them with calm, certain confidence that it will do what it always has done -- accomplish its mission.

February 11. 2011 by Kenneth Slawenski (vanityfair.com)

As part of the 4th Counter Intelligence Corps (C.I.C.) detachment, J.D.Salinger was to land on Utah Beach with the first wave, at 6:30 A.M., but an eyewitness report has him in fact landing during the second wave, about 10 minutes later. The timing was fortunate. The Channel’s currents had thrown the landing off 2,000 yards to the south, allowing Salinger to avoid the most heavily concentrated German defenses. Within an hour of landing, Salinger was moving inland and heading west, where he and his detachment would eventually connect with the 12th Infantry Regiment.

The 12th had not been so lucky. Although it landed five hours later, it had encountered obstacles that Salinger and his group had not. Just beyond the beach, the Germans had flooded a vast marshland, up to two miles wide, and had concentrated their firepower on the only open causeway. The 12th had been forced to abandon the causeway and wade through waist-high water while under constant threat from enemy guns. It took the 12th Infantry three hours to cross the marsh. After meeting up with the regiment, Salinger would spend the next 26 days in combat. On June 6, the regiment had consisted of 3,080 men. By July 1, the number was down to 1,130.

As part of the 4th Counter Intelligence Corps (C.I.C.) detachment, J.D.Salinger was to land on Utah Beach with the first wave, at 6:30 A.M., but an eyewitness report has him in fact landing during the second wave, about 10 minutes later. The timing was fortunate. The Channel’s currents had thrown the landing off 2,000 yards to the south, allowing Salinger to avoid the most heavily concentrated German defenses. Within an hour of landing, Salinger was moving inland and heading west, where he and his detachment would eventually connect with the 12th Infantry Regiment.

The 12th had not been so lucky. Although it landed five hours later, it had encountered obstacles that Salinger and his group had not. Just beyond the beach, the Germans had flooded a vast marshland, up to two miles wide, and had concentrated their firepower on the only open causeway. The 12th had been forced to abandon the causeway and wade through waist-high water while under constant threat from enemy guns. It took the 12th Infantry three hours to cross the marsh. After meeting up with the regiment, Salinger would spend the next 26 days in combat. On June 6, the regiment had consisted of 3,080 men. By July 1, the number was down to 1,130.

Utah Beach

History of the beach

Utah Beach is the first of the two American landing zones. This beach was wanted by the english general Bernard Montgomery who wished to establish a beachhead directly in the Cotentin, in order to capture Cherbourg faster, since it has a deep water harbor.

Involved forces

There are two sectors on Utah: Uncle Red and Tare Green, located between the village of Dunes-de-Varreville (North) and La Madeleine (South). These beaches are defended by the 709th german infantry division which has installed 7 strongpoints and 20 batteries. Two artillery batteries, located at Montebourg and Saint-Marcouf, can open fire on this beach, since these guns have a firing range of almost 30 kilometers.

It is the 7th Army of the Major General J. Lawton Collins, composed of the 8th, 22nd and 12nd infantry regiments of the 4th american infantry division led by the general Omar C. Bradley, commanding the 1st American Army, which will launch the attack of Utah Beach on D-Day in order to capture the landing beach sectors, then to establish a solid beachhead and to carry out the junction with the airborne troops of the 82nd and

The attack has to be done early in the morning, at 06:30 a.m., a schedule which corresponds to a very low tide: then the German beach obstacles (which represent a very important danger for the navy) are uncovered. Also, the engineers can open ways on the beach through these obstacles in order to allow the following reinforcements to land.

The attack

Tuesday June 6, at 3 o'clock in the morning, the U fleet (Utah) arrives near the Cotentin beaches and damps at approximately 18 kilometers off the coast, a distance which limits the effectiveness of the German batteries.

The day comes at 05:58 a.m. exactly, 28 minutes after the beginning of the bombardment of the German positions by the allied warships. This huge bombardment follows air raids carried out by thousand of allied bombers.

The American soldiers of the 4th infantry division who boarded the landing crafts can see these bombardments which plow the French ground and which fill up the sky with smoke. Even if much of them suffer from a terrible sea sickness, they are glad to see the bunkers becoming dust.

Two squadrons of Duplex Drive tanks start floating 3 kilometers off the shore and must join the beach sectors by their own means thanks to two propellers and a rubber protection which enable them to sail towards their objective. They approach the beach in two assault waves (the first one is made up of 12 D.D. tanks and the second one of 16) and when the Germans reorganize after the terrible allied bombardment, they discover American tanks coming from the sea and moving to their positions.

The first American assault wave lands right after the arrival of the tanks in order to be supported in their action. Then, they attack the bunkers and blockhouses of Utah Beach.

During the first minutes of the landing on Utah Beach, the German shootings are important but soon, the light and heavy German machineguns stop firing. Then, long distance guns belonging to the 709th German infantry division, situated a few kilometers inland, open fire.

These guns open fire from the positions located a few kilometers West from the landing beach and are camouflaged so that the allied planes which patrol in the Norman sky can not locate them.

History of the beach

Utah Beach is the first of the two American landing zones. This beach was wanted by the english general Bernard Montgomery who wished to establish a beachhead directly in the Cotentin, in order to capture Cherbourg faster, since it has a deep water harbor.

Involved forces

There are two sectors on Utah: Uncle Red and Tare Green, located between the village of Dunes-de-Varreville (North) and La Madeleine (South). These beaches are defended by the 709th german infantry division which has installed 7 strongpoints and 20 batteries. Two artillery batteries, located at Montebourg and Saint-Marcouf, can open fire on this beach, since these guns have a firing range of almost 30 kilometers.

It is the 7th Army of the Major General J. Lawton Collins, composed of the 8th, 22nd and 12nd infantry regiments of the 4th american infantry division led by the general Omar C. Bradley, commanding the 1st American Army, which will launch the attack of Utah Beach on D-Day in order to capture the landing beach sectors, then to establish a solid beachhead and to carry out the junction with the airborne troops of the 82nd and

The attack has to be done early in the morning, at 06:30 a.m., a schedule which corresponds to a very low tide: then the German beach obstacles (which represent a very important danger for the navy) are uncovered. Also, the engineers can open ways on the beach through these obstacles in order to allow the following reinforcements to land.

The attack

Tuesday June 6, at 3 o'clock in the morning, the U fleet (Utah) arrives near the Cotentin beaches and damps at approximately 18 kilometers off the coast, a distance which limits the effectiveness of the German batteries.

The day comes at 05:58 a.m. exactly, 28 minutes after the beginning of the bombardment of the German positions by the allied warships. This huge bombardment follows air raids carried out by thousand of allied bombers.

The American soldiers of the 4th infantry division who boarded the landing crafts can see these bombardments which plow the French ground and which fill up the sky with smoke. Even if much of them suffer from a terrible sea sickness, they are glad to see the bunkers becoming dust.

Two squadrons of Duplex Drive tanks start floating 3 kilometers off the shore and must join the beach sectors by their own means thanks to two propellers and a rubber protection which enable them to sail towards their objective. They approach the beach in two assault waves (the first one is made up of 12 D.D. tanks and the second one of 16) and when the Germans reorganize after the terrible allied bombardment, they discover American tanks coming from the sea and moving to their positions.

The first American assault wave lands right after the arrival of the tanks in order to be supported in their action. Then, they attack the bunkers and blockhouses of Utah Beach.

During the first minutes of the landing on Utah Beach, the German shootings are important but soon, the light and heavy German machineguns stop firing. Then, long distance guns belonging to the 709th German infantry division, situated a few kilometers inland, open fire.

These guns open fire from the positions located a few kilometers West from the landing beach and are camouflaged so that the allied planes which patrol in the Norman sky can not locate them.

Very quickly, the beach is under American control. The tide is low, German beach defenses are visible on a distance of 500 meters between the dunes and the sea. The fifth and last assault wave lands half an hour after H Hour. One hour after H Hour, at 07:30 a.m., some engineers open breaches through the beach obstacles so that the landing barges can sail without troubles.

Assessment

At the end of the day in Utah Beach, on June 6, 1944, 1,700 vehicles have landed and also nearly 23,250 american soldiers. 197 soldiers have been killed and 60 are missing.

Assessment

At the end of the day in Utah Beach, on June 6, 1944, 1,700 vehicles have landed and also nearly 23,250 american soldiers. 197 soldiers have been killed and 60 are missing.

NOTE: A detail accounting of the first objective for the 4th Div upon landing, the taking of Cherbourg, called Utah Beach to Cherbourg, takes account in detail the events of June 6 - 27th, 1944. This article was written by the Center of Military History, U.S. Army. 1990

The description of the battle for the Hurtgen Forest, is the actual location where the 2/12th earned their Presidental Unit Citation as part of the Battle of the Bulge, although the campaign to take this area from the Germans started in November with the 28th Div, a month earlier, but became the longer battle of the war. The 2/12th was sent as a relief unit when the 28th Div was in trouble - Sarge

The description of the battle for the Hurtgen Forest, is the actual location where the 2/12th earned their Presidental Unit Citation as part of the Battle of the Bulge, although the campaign to take this area from the Germans started in November with the 28th Div, a month earlier, but became the longer battle of the war. The 2/12th was sent as a relief unit when the 28th Div was in trouble - Sarge

Slide Show of Utah Beach on June 6, 1944

Roll mouse over map to enlarge

A strong current

Brigadier general Theodore Roosevelt, nephew of the president of the United States, lands with the first assault wave. He realizes very quickly with the HQ staff of the 4th infantry division, that the marine current has moved the landing two kilometers south of the planned landing beach location. Indeed, they are not located north but south of La Madeleine, in front of the German W5 strongpoint.

The problem with this improvised landing area is that there is only one small road going out the beach from the dunes whereas in the planned beach sector there are four roads heading inland, which was better for the reinforcements. The question is: will the reinforcements follow the first plan or will they adapt themself and follow the new beach sector, south of the village of La Madeleine? Roosevelt indicates that the reinforcements must follow the assault troops whatever the landing point.

On the other hand, the W5 strongpoint resistance is less important than the one north of La Madeleine and all the attacks to the north are pushed back by the german forces, supported by the shootings of the Kriegsmarine batteries from Montebourg and Saint-Marcouf. Roosevelt decides to move inland using this only road controlled by the Americans, despite the risks of obstructions. Indeed, 30,000 American soldiers and 3,500 vehicles have to landed at Utah Beach on D-Dat and the simple country lane, between the grounds flooded by the Germans, seems insufficient to support such a quantity of troops and material.

Meanwhile, American tanks wait on the beach until the engineers destroy the anti-tank walls, then they can move on. Two hours after H Hour, at 08:30 a.m., they cross the dune and move towards Normandy.

If the shootings on the beaches become rare, the explosions of german mortar and artillery shells continue to kill. This bombardment continues until the end of the evening.

Brigadier general Theodore Roosevelt, nephew of the president of the United States, lands with the first assault wave. He realizes very quickly with the HQ staff of the 4th infantry division, that the marine current has moved the landing two kilometers south of the planned landing beach location. Indeed, they are not located north but south of La Madeleine, in front of the German W5 strongpoint.

The problem with this improvised landing area is that there is only one small road going out the beach from the dunes whereas in the planned beach sector there are four roads heading inland, which was better for the reinforcements. The question is: will the reinforcements follow the first plan or will they adapt themself and follow the new beach sector, south of the village of La Madeleine? Roosevelt indicates that the reinforcements must follow the assault troops whatever the landing point.

On the other hand, the W5 strongpoint resistance is less important than the one north of La Madeleine and all the attacks to the north are pushed back by the german forces, supported by the shootings of the Kriegsmarine batteries from Montebourg and Saint-Marcouf. Roosevelt decides to move inland using this only road controlled by the Americans, despite the risks of obstructions. Indeed, 30,000 American soldiers and 3,500 vehicles have to landed at Utah Beach on D-Dat and the simple country lane, between the grounds flooded by the Germans, seems insufficient to support such a quantity of troops and material.

Meanwhile, American tanks wait on the beach until the engineers destroy the anti-tank walls, then they can move on. Two hours after H Hour, at 08:30 a.m., they cross the dune and move towards Normandy.

If the shootings on the beaches become rare, the explosions of german mortar and artillery shells continue to kill. This bombardment continues until the end of the evening.

D Day D Day plus 1

Roll mouse over maps to enlarge

The D-Day Landing in Retrospect

The relative ease with which the assault on Utah Beach was accomplished was surprising even to the attackers, and gave the lie to the touted impregnability of the Atlantic Wall. The 4th Division's losses for D Day were astonishingly low. The 8th and 22d Infantry Regiments, which landed before noon, suffered a total of 118 casualties on D Day, 12 of them fatalities. The division as a whole suffered only 197 casualties during the day, and these included 60 men missing through the loss (at sea) of part of Battery B, 29th Field Artillery Battalion. Not less noteworthy than the small losses was the speed of the landings. With the exception of one field artillery battalion (the 20th) the entire 4th Division had landed in the first fifteen hours. In addition there came ashore one battalion of the 359th Infantry, the 65th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, the 87th Chemical Mortar Battalion, the 899th Tank Destroyer Battalion (less two companies), the 70th and 746th Tank Battalions, components of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade which had begun organizing the beach for the build-up, seaborne elements of the airborne divisions, and many smaller units. A total of over 20,000 troops and 1,700 vehicles reached Utah Beach by the end of 6 June.

Corps headquarters had, up to the night of D Day, participated but very little in the initial beachhead operation. Consequently, all activity centered around the divisions and, more particularly, their subordinate units.