LTC Richard R Gary

4th Brigade Combat Team

"Warrior Brigade"

"Warrior Brigade"

Home of the 2-12th Inf Regiment

The 2-12th Inf Regiment

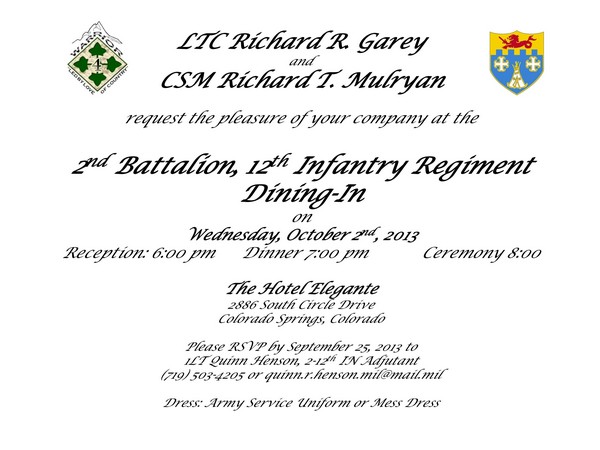

The 2/12th held a Dining In event on October 2nd, 2013. LTC Garey and CSM Mulryan extended an invitation to a number of Vietnam veterans. Steve Ward (Co C 1968), Bill Braniff (Co A 1968), Craig Schoonderwoerd (Co C 1968) and myself, Arnold Krause (Co C 1968) accepted the invitation. Upon arriving at the hotel, after check-in, we were greeted by 1LT Quinn Henson, 2/12th who then discussed how the evenings events would play out and what and where we needed to be.

The evening started with a no host cocktail hour then it was announced that the “Mess” was open. This was a blue dress uniform affair and no wives could attend. We were seated at the head table with LTC Richard Garey, BN C.O., BN CSM Richard Mulryan, MJR Mcallister BN XO and MJR Spears BN S3. After the colors were posted, the guests were introduced to the battalion (approx 560 men and women) and their bio’s read. The next portion of the ceremony, were toasts given to the President, Army, Infantry, Division, Brigade, Battalion, Veterans, fallen veterans and to those who came before us. The Grog bowl was then filled with various ingredients that represented each campaign in which the unit has served since its inception. Some kidding was done in fun prior to dinner being served.

After dinner and a brief break, Bill Braniff and Arnold Krause were introduced to the battalion by LTC Garey. Bill talked about his pursuit of finding Eugene Handrahan, the only MIA in Vietnam from our unit and what he was trying to do to locate the remains and provide this information to JPAC who is the official unit responsible and charged with this task by Congress. Bill has returned to Vietnam about 50 times at his own expense. Following Bill’s talk, Arnold Krause took the podium as the guest speaker. He talked for 15 minutes thanking those who are serving today, then led the audience back to 1968 where he talked about how the war was fought and what the conditions were like. In closing, he reminded the troops of the importance of keeping contact with those who served, getting help if needed and a salute to all members who served and are serving in closing. LTC Garey then presented a lithograph of the unit in action in Afhganistan to each of the guests. A copy of the speech can be read by clicking here on Ft Carson.

After the guest speakers and closing remarks by LTC Garey, the “Mess” was closed. During the entire event, we had a photographer (LT Le) who took many pictures of the evening. A photo shoot followed the event in front of the guest seating area. The single action that impressed us the most was having nearly every single officer and NCO in the battalion come up to each of us and shake our hands and tell us how HONORED they were to meet us. They expressed their gratitude by saying how much we have led the way for them by example and how much more difficult we had it than they did. This shaking of hands continued until we were the last men standing around 1AM. For us, it had to be the single most humbling experience any of us have had since returning from Vietnam. The words cannot describe how each of us felt that evening sitting there in front of the entire battalion, then receiving an ovation and later, the handshakes.

I was told by many that the speech I gave hit home and was well received by everyone who listened. I am not sure how long it will resonate with each of the soldiers, but for the night and the experience, it was worth every minute I stood in front of them as I talked. This was certainly near the top for anything I have ever done in my lifetime. To speak to such a large audience about a subject most of them could relate to, comrades in arms and brothers banded by war.

The evening started with a no host cocktail hour then it was announced that the “Mess” was open. This was a blue dress uniform affair and no wives could attend. We were seated at the head table with LTC Richard Garey, BN C.O., BN CSM Richard Mulryan, MJR Mcallister BN XO and MJR Spears BN S3. After the colors were posted, the guests were introduced to the battalion (approx 560 men and women) and their bio’s read. The next portion of the ceremony, were toasts given to the President, Army, Infantry, Division, Brigade, Battalion, Veterans, fallen veterans and to those who came before us. The Grog bowl was then filled with various ingredients that represented each campaign in which the unit has served since its inception. Some kidding was done in fun prior to dinner being served.

After dinner and a brief break, Bill Braniff and Arnold Krause were introduced to the battalion by LTC Garey. Bill talked about his pursuit of finding Eugene Handrahan, the only MIA in Vietnam from our unit and what he was trying to do to locate the remains and provide this information to JPAC who is the official unit responsible and charged with this task by Congress. Bill has returned to Vietnam about 50 times at his own expense. Following Bill’s talk, Arnold Krause took the podium as the guest speaker. He talked for 15 minutes thanking those who are serving today, then led the audience back to 1968 where he talked about how the war was fought and what the conditions were like. In closing, he reminded the troops of the importance of keeping contact with those who served, getting help if needed and a salute to all members who served and are serving in closing. LTC Garey then presented a lithograph of the unit in action in Afhganistan to each of the guests. A copy of the speech can be read by clicking here on Ft Carson.

After the guest speakers and closing remarks by LTC Garey, the “Mess” was closed. During the entire event, we had a photographer (LT Le) who took many pictures of the evening. A photo shoot followed the event in front of the guest seating area. The single action that impressed us the most was having nearly every single officer and NCO in the battalion come up to each of us and shake our hands and tell us how HONORED they were to meet us. They expressed their gratitude by saying how much we have led the way for them by example and how much more difficult we had it than they did. This shaking of hands continued until we were the last men standing around 1AM. For us, it had to be the single most humbling experience any of us have had since returning from Vietnam. The words cannot describe how each of us felt that evening sitting there in front of the entire battalion, then receiving an ovation and later, the handshakes.

I was told by many that the speech I gave hit home and was well received by everyone who listened. I am not sure how long it will resonate with each of the soldiers, but for the night and the experience, it was worth every minute I stood in front of them as I talked. This was certainly near the top for anything I have ever done in my lifetime. To speak to such a large audience about a subject most of them could relate to, comrades in arms and brothers banded by war.

Speech given by Arnold Krause............

Good evening. On behalf of my fellow veterans, I would like to thank Col Garey, the officers, Lt Henson who worked to get us here, CSM Mulryan and you, the enlisted men of the 2/12th for making this possible. I looked in the mirror earlier today and then I look at you and thought to myself, “where has the time gone?” You are me; you are us (gesture) 45 years later. I never thought or visualized that I would ever be standing here now giving a talk.

All Americans, but especially veterans, are proud of the men and women who serve today. We understand the sacrifices that the military must embrace in both peace and war. We are grateful for your willingness to serve and for the courage that you and this unit have displayed in Iraq & Afghanistan, and in fulfilling your mission objectives in difficult times.

The recognition and gratitude conveyed by the U.S. Government and the American people that you have so deservingly received is why public opinion turned from a negative to a positive for the Vietnam Veteran. We did not come home to any fan fair nor were we the recipients of public praise and appreciation. For most returning veterans, we quickly removed our uniforms and quietly slide back into private life. The government turned it back to us in every possible way and wanted to forget all about this war. It was the first time in American history that young American soldiers were not respected or honored in the ways we should have been unlike those who fought in WWII and Korea. Little was taught in schools about the history of the Vietnam War, but now that is changing. Today public opinion is overwhelmingly favorable.

Each war is different and every veteran has his own story to tell. Vietnam, like Afghanistan, was mostly guerilla warfare, where half the time the enemy looked the same as the farmer in the field because he was. Half the time, the only way to know the enemy, was when the bullets started flying. Most of the time, they did not wear uniforms of any type. White shirts, no shirts, black tops and pajama bottoms or maybe just black shorts and ho chi minh sandals. Hats, no hats, jungle hats, head scarfs, conical rice hats.

This was a game of hide and seek by the enemy. They wanted to control the place and time for fights where they had the upper hand and an escape route if the engagement did not go well. Sniper fire and ambushes were at the top of their tactical list. Most of the contact was against smaller VC guerilla units; snipers, squads and platoon sized elements. Their unit strengths were similar to ours. When the VC or NVA chose to take us on in strength, the numbers grew to company or battalion sized attacks. The Battle at Suoi Tre involved over 2500 enemy soldiers. Many of these larger engagements attempted to over run a night defensive position or a fire support base which was usually defended by two to four U.S. companies. There were many times we made contact in the daytime, and then were told to remain in the area and set up a night laager site. If the unit size was small, such as two platoons, it would be reinforced until it was manned by no less than company strength. We became the bait. Battalion would fly out a “night kit” containing concertina wire and claymore mines which we hastily strung to make a perimeter, then started digging our foxholes and doing what we could to make firing positions then waited. We respected the VC as a tough and determined enemy who was willing to die for his beliefs and demonstrated it time and again. They had no fear and the women soldiers were just as loyal in their determination to win.

Although many men joined the service throughout the war, everyone over 18 had to register for the draft which then entered you into a lottery system and you hoped they didn’t select your number. Not everyone’s career choice was the military leaving school especially during a war. If you got selected, it meant two years of active duty and four in the reserve, although those who faced combat ended up excused from reserve duty after they left the service. About 1 out of 4 who served in Vietnam, were drafted. The war had some popular support in the beginning, and then over time, the bickering started and grew into a movement, the peace movement. The politicians argued, the population grew restless and the guys fighting on the ground heard all this and wondered what is going on. We’re supposed to be fighting to win, but somehow we don’t sense it.

For those of us in “the line units” we spent very little time in buildings or in camps with permanent structures. We were out in the field day and night. Security patrols, recon’s in force, search and destroy missions, combat assaults then night ambushes followed by day patrols then more night ambushes. We were short on sleep often so naps were taken whenever we could and anywhere. The dry season was hot with temperatures in the 80’s and 90’s or and we sweated until our fatigues seemed like they couldn’t dry out. When the Monsoon season arrived it rained every day. We walked in water and flooded rice paddies day and night. No one tried to stay dry because that was impossible. We just tried to minimize how long we stayed wet to keep from getting skin infections.

The geography we operated in varied from jungle terrain, rubber plantations that stretched for miles, mountains, then later the open rice fields surrounded by hedgerows and groves of trees. Scattered throughout all of this were the villages and hamlets that harbored both friend and foe. From the Cambodian border which we ultimately breached in 1970, to the edge of Saigon we patrolled, searched and fought. When we were not seeking out the enemy, we tried to build a relationship with the local villagers by running MEDCAP’s where we treated the people of the hamlets with medical care, tended to their ailments and administered shots. The children were a delight and always worth a smile or laugh. They loved to sell us soda and ice and followed us around.

Our average field strength for a company varied between 80-100 men not including the heavy weapons platoon (81 and 4.2 mortars). Platoons were around 25-30 men. My company, Charlie Company had 397 men listed on the rosters over the course of the year I was there and I’m sure it was that way for most of the companies. That’s a 400 percent turnover ratio. Wounded men who were sent home, those who’s tours were up, sickness, death from natural causes, occasionally self inflected wounds, transfers and those who died on the battlefield all contributed to that turnover.

At first many of us could only think of home and how long it would be before we would see it again. We were almost obsessed by this thought. I could not remember many who was in my platoon until I was in country for 2 months. The faces were constantly changing which didn’t help either. Over time, that all slowed down and I stopped thinking about the “world (home) and focused on the mission. Over the latter part of my tour, the names and faces began to stick. My ability to recall names improved. Over time we learned to trust and respect each other and at the same time were reluctant to make close friends. We did not want to grieve if we lost someone and yet that was the reality. We tried to simplify our lives as best we could to keep our sanity. But that was not possible. We did care a whole bunch for each other.

The fire fights were constant at times with one of the company’s always making contact and the combat assaults frequent. Dealing with the wounded was often and we had our losses too. If it wasn’t the buzz of the enemy’s bullets or the numerous use of RPG’s against us, it was the booby traps. Punji stakes to step on or traps dug to fall into. Trip wires everywhere we walked and someone always managed to trigger one. We kept our eyes out for hidden bunkers, spider holes, trap doors and tunnel complexes to hide in. There were the snakes, scorpions, crawling insects, mosquitoes, leaches in the water and water buffalo that hated the smell of us. Cornering the enemy at times was like trying to kill a gopher that was living in your lawn and digging up your yard. Always keep your guard up and look for movement to your front. Always look where you are going and where you are stepping and stay off the trails. Never walk through an area the same way twice. And then there were our life savers, the medics who gave and cared so much. They dressed our wounds or made sure we were we taking care of ourselves and checked to be sure we took our pills for malaria weekly.

But what put a smile on our faces was those hueys and hearing that WAP WAP WAP of the rotor blades of a gunship in the distance or maybe a chopper that came into a hot LZ to resupply us during a fight. And for those moments when we needed it, a MEDEVAC to pick up the wounded or the dead. Sometimes it was just to pick us up and carry us back to somewhere safe.

We shared our c-rations, water and cigarettes and had each other’s backs when it counted. We got a change of clothing about every two weeks or so and usually had a hot meal several times a week that was flown out to us if we were in the boonies on a mission. In a fire support base, if it was intended to be there for awhile, we might have a mess tent to pick up some hot chow. We couldn’t always brush our teeth and we gave each other haircuts. Showers were limited to when it rained in the field or when we put water in a steel pot and used a rag to wash. Sometimes we had overhead showers from a canvas bucket, but we made do. Toilets were a behind a bush, a couple of boards set up over a latrine or maybe a three holer in a base camp. Mail call was special because that was our only connection to the ‘world’ outside of listening to the Armed Forces radio at night. We wrote letters to Mom and Dad, to our siblings and friends and told them we were OK, but not really writing about what we were doing or how it was in Vietnam. There was neither internet nor satellite cell service to home back then.

We learned about warfare the hard way because many of us were not career soldiers. Our leadership had to be forged the same way we created NCO’s - on the battlefield. It was a constant struggle. Personally for me, I had 5 C.O.’s, 6 platoon leaders and 3 plt sgts (4 counting myself) during my tour. You need to take care of each other. The pressures are enormous. Some handle it better than others. Don’t be afraid to get help if you need it after your tours, or when your career ends. The VA took a long time to respond to our needs. It took the Supreme Court to make the government accountable for our exposure to Agent Orange. Many Vietnam Vets still need help and refuse to get it. Don’t fall into that camp. Embrace your time in the military and wear your uniform proudly. When people ask you questions, the more you talk about your experiences the better you are off mentally. Everyone is in a different state of mind before something bad happens and certainly that is no different afterwards. What sets people apart is their mental toughness and ability to recognize, accept, and then leave situations behind them. The degree to which that happens or not is the measure of one’s combat effectiveness.

We had a tendency to NOT want to remember or record what was going on during our tour but to forget our experiences like a bad nightmare. Years later, many of us regret not keeping a diary of some kind so we could remember details later, both the good and the bad. Most of us did not carry around cameras on patrol. A few guys did and I always wondered “what is he thinking? But afterwards, many years later, seeing some of those photos is priceless. They do have their place but I will not tell you when because the situation would dictate that. Through the website I created to memorialize our time in Vietnam, I often get requests from family members who want pictures of their loved ones who died. They appreciate knowing how they fit in and what kind of soldier they were and what happened to them. Keep track of names, where guys are from and their addresses. At some point you may want to reconnect and can’t because all you can remember is the guy’s last name and nothing else. I know because I am trying to find old buddies today. What seems unimportant now will look much different as you grow older and as you begin to appreciate what it was that you went through and who you share that experience with. Trust me when I say that. That’s the way it was for us. It may be a bit different today with your cell phones and the internet available. If so, just remember to call and stay in touch.

Your military career puts you in a unique place, now and when you leave the service. I trust and hope that as you grow older, you will continue to support the service and fellow veterans in some way. I echo this single word, remember. Remember those who are serving as you now do yourself. Remember to lend a helping hand. Remember to stop what you are doing and listen. Remember to offer financial assistance to those who may be struggling. Remember they are all brothers and sisters and those relationships will last for your lifetime.

The bonds created by your military service and by war are forged so deep that nothing can ever break that. Bonded by war, brothers forever. The sweat that poured off of us, the tears we shed, the fear we felt, the courage displayed, the blood that was spilt is forever cast in our minds. To those who served in the past, and to those who serve today, the tradition and honor lives on. A fact that was lost because of our youth and how quickly we wanted to put our war behind us, and the public sentiment at the time, but later we regained that pride and understanding of what it meant to be a soldier and a combat veteran. To those Warriors who have fought and died, to the men we knew and lost, we will never forget you. To those who have served with honor and distinction hold fast to our motto – Having been lead by love of country. We salute you one and all.

Thank you.

Good evening. On behalf of my fellow veterans, I would like to thank Col Garey, the officers, Lt Henson who worked to get us here, CSM Mulryan and you, the enlisted men of the 2/12th for making this possible. I looked in the mirror earlier today and then I look at you and thought to myself, “where has the time gone?” You are me; you are us (gesture) 45 years later. I never thought or visualized that I would ever be standing here now giving a talk.

All Americans, but especially veterans, are proud of the men and women who serve today. We understand the sacrifices that the military must embrace in both peace and war. We are grateful for your willingness to serve and for the courage that you and this unit have displayed in Iraq & Afghanistan, and in fulfilling your mission objectives in difficult times.

The recognition and gratitude conveyed by the U.S. Government and the American people that you have so deservingly received is why public opinion turned from a negative to a positive for the Vietnam Veteran. We did not come home to any fan fair nor were we the recipients of public praise and appreciation. For most returning veterans, we quickly removed our uniforms and quietly slide back into private life. The government turned it back to us in every possible way and wanted to forget all about this war. It was the first time in American history that young American soldiers were not respected or honored in the ways we should have been unlike those who fought in WWII and Korea. Little was taught in schools about the history of the Vietnam War, but now that is changing. Today public opinion is overwhelmingly favorable.

Each war is different and every veteran has his own story to tell. Vietnam, like Afghanistan, was mostly guerilla warfare, where half the time the enemy looked the same as the farmer in the field because he was. Half the time, the only way to know the enemy, was when the bullets started flying. Most of the time, they did not wear uniforms of any type. White shirts, no shirts, black tops and pajama bottoms or maybe just black shorts and ho chi minh sandals. Hats, no hats, jungle hats, head scarfs, conical rice hats.

This was a game of hide and seek by the enemy. They wanted to control the place and time for fights where they had the upper hand and an escape route if the engagement did not go well. Sniper fire and ambushes were at the top of their tactical list. Most of the contact was against smaller VC guerilla units; snipers, squads and platoon sized elements. Their unit strengths were similar to ours. When the VC or NVA chose to take us on in strength, the numbers grew to company or battalion sized attacks. The Battle at Suoi Tre involved over 2500 enemy soldiers. Many of these larger engagements attempted to over run a night defensive position or a fire support base which was usually defended by two to four U.S. companies. There were many times we made contact in the daytime, and then were told to remain in the area and set up a night laager site. If the unit size was small, such as two platoons, it would be reinforced until it was manned by no less than company strength. We became the bait. Battalion would fly out a “night kit” containing concertina wire and claymore mines which we hastily strung to make a perimeter, then started digging our foxholes and doing what we could to make firing positions then waited. We respected the VC as a tough and determined enemy who was willing to die for his beliefs and demonstrated it time and again. They had no fear and the women soldiers were just as loyal in their determination to win.

Although many men joined the service throughout the war, everyone over 18 had to register for the draft which then entered you into a lottery system and you hoped they didn’t select your number. Not everyone’s career choice was the military leaving school especially during a war. If you got selected, it meant two years of active duty and four in the reserve, although those who faced combat ended up excused from reserve duty after they left the service. About 1 out of 4 who served in Vietnam, were drafted. The war had some popular support in the beginning, and then over time, the bickering started and grew into a movement, the peace movement. The politicians argued, the population grew restless and the guys fighting on the ground heard all this and wondered what is going on. We’re supposed to be fighting to win, but somehow we don’t sense it.

For those of us in “the line units” we spent very little time in buildings or in camps with permanent structures. We were out in the field day and night. Security patrols, recon’s in force, search and destroy missions, combat assaults then night ambushes followed by day patrols then more night ambushes. We were short on sleep often so naps were taken whenever we could and anywhere. The dry season was hot with temperatures in the 80’s and 90’s or and we sweated until our fatigues seemed like they couldn’t dry out. When the Monsoon season arrived it rained every day. We walked in water and flooded rice paddies day and night. No one tried to stay dry because that was impossible. We just tried to minimize how long we stayed wet to keep from getting skin infections.

The geography we operated in varied from jungle terrain, rubber plantations that stretched for miles, mountains, then later the open rice fields surrounded by hedgerows and groves of trees. Scattered throughout all of this were the villages and hamlets that harbored both friend and foe. From the Cambodian border which we ultimately breached in 1970, to the edge of Saigon we patrolled, searched and fought. When we were not seeking out the enemy, we tried to build a relationship with the local villagers by running MEDCAP’s where we treated the people of the hamlets with medical care, tended to their ailments and administered shots. The children were a delight and always worth a smile or laugh. They loved to sell us soda and ice and followed us around.

Our average field strength for a company varied between 80-100 men not including the heavy weapons platoon (81 and 4.2 mortars). Platoons were around 25-30 men. My company, Charlie Company had 397 men listed on the rosters over the course of the year I was there and I’m sure it was that way for most of the companies. That’s a 400 percent turnover ratio. Wounded men who were sent home, those who’s tours were up, sickness, death from natural causes, occasionally self inflected wounds, transfers and those who died on the battlefield all contributed to that turnover.

At first many of us could only think of home and how long it would be before we would see it again. We were almost obsessed by this thought. I could not remember many who was in my platoon until I was in country for 2 months. The faces were constantly changing which didn’t help either. Over time, that all slowed down and I stopped thinking about the “world (home) and focused on the mission. Over the latter part of my tour, the names and faces began to stick. My ability to recall names improved. Over time we learned to trust and respect each other and at the same time were reluctant to make close friends. We did not want to grieve if we lost someone and yet that was the reality. We tried to simplify our lives as best we could to keep our sanity. But that was not possible. We did care a whole bunch for each other.

The fire fights were constant at times with one of the company’s always making contact and the combat assaults frequent. Dealing with the wounded was often and we had our losses too. If it wasn’t the buzz of the enemy’s bullets or the numerous use of RPG’s against us, it was the booby traps. Punji stakes to step on or traps dug to fall into. Trip wires everywhere we walked and someone always managed to trigger one. We kept our eyes out for hidden bunkers, spider holes, trap doors and tunnel complexes to hide in. There were the snakes, scorpions, crawling insects, mosquitoes, leaches in the water and water buffalo that hated the smell of us. Cornering the enemy at times was like trying to kill a gopher that was living in your lawn and digging up your yard. Always keep your guard up and look for movement to your front. Always look where you are going and where you are stepping and stay off the trails. Never walk through an area the same way twice. And then there were our life savers, the medics who gave and cared so much. They dressed our wounds or made sure we were we taking care of ourselves and checked to be sure we took our pills for malaria weekly.

But what put a smile on our faces was those hueys and hearing that WAP WAP WAP of the rotor blades of a gunship in the distance or maybe a chopper that came into a hot LZ to resupply us during a fight. And for those moments when we needed it, a MEDEVAC to pick up the wounded or the dead. Sometimes it was just to pick us up and carry us back to somewhere safe.

We shared our c-rations, water and cigarettes and had each other’s backs when it counted. We got a change of clothing about every two weeks or so and usually had a hot meal several times a week that was flown out to us if we were in the boonies on a mission. In a fire support base, if it was intended to be there for awhile, we might have a mess tent to pick up some hot chow. We couldn’t always brush our teeth and we gave each other haircuts. Showers were limited to when it rained in the field or when we put water in a steel pot and used a rag to wash. Sometimes we had overhead showers from a canvas bucket, but we made do. Toilets were a behind a bush, a couple of boards set up over a latrine or maybe a three holer in a base camp. Mail call was special because that was our only connection to the ‘world’ outside of listening to the Armed Forces radio at night. We wrote letters to Mom and Dad, to our siblings and friends and told them we were OK, but not really writing about what we were doing or how it was in Vietnam. There was neither internet nor satellite cell service to home back then.

We learned about warfare the hard way because many of us were not career soldiers. Our leadership had to be forged the same way we created NCO’s - on the battlefield. It was a constant struggle. Personally for me, I had 5 C.O.’s, 6 platoon leaders and 3 plt sgts (4 counting myself) during my tour. You need to take care of each other. The pressures are enormous. Some handle it better than others. Don’t be afraid to get help if you need it after your tours, or when your career ends. The VA took a long time to respond to our needs. It took the Supreme Court to make the government accountable for our exposure to Agent Orange. Many Vietnam Vets still need help and refuse to get it. Don’t fall into that camp. Embrace your time in the military and wear your uniform proudly. When people ask you questions, the more you talk about your experiences the better you are off mentally. Everyone is in a different state of mind before something bad happens and certainly that is no different afterwards. What sets people apart is their mental toughness and ability to recognize, accept, and then leave situations behind them. The degree to which that happens or not is the measure of one’s combat effectiveness.

We had a tendency to NOT want to remember or record what was going on during our tour but to forget our experiences like a bad nightmare. Years later, many of us regret not keeping a diary of some kind so we could remember details later, both the good and the bad. Most of us did not carry around cameras on patrol. A few guys did and I always wondered “what is he thinking? But afterwards, many years later, seeing some of those photos is priceless. They do have their place but I will not tell you when because the situation would dictate that. Through the website I created to memorialize our time in Vietnam, I often get requests from family members who want pictures of their loved ones who died. They appreciate knowing how they fit in and what kind of soldier they were and what happened to them. Keep track of names, where guys are from and their addresses. At some point you may want to reconnect and can’t because all you can remember is the guy’s last name and nothing else. I know because I am trying to find old buddies today. What seems unimportant now will look much different as you grow older and as you begin to appreciate what it was that you went through and who you share that experience with. Trust me when I say that. That’s the way it was for us. It may be a bit different today with your cell phones and the internet available. If so, just remember to call and stay in touch.

Your military career puts you in a unique place, now and when you leave the service. I trust and hope that as you grow older, you will continue to support the service and fellow veterans in some way. I echo this single word, remember. Remember those who are serving as you now do yourself. Remember to lend a helping hand. Remember to stop what you are doing and listen. Remember to offer financial assistance to those who may be struggling. Remember they are all brothers and sisters and those relationships will last for your lifetime.

The bonds created by your military service and by war are forged so deep that nothing can ever break that. Bonded by war, brothers forever. The sweat that poured off of us, the tears we shed, the fear we felt, the courage displayed, the blood that was spilt is forever cast in our minds. To those who served in the past, and to those who serve today, the tradition and honor lives on. A fact that was lost because of our youth and how quickly we wanted to put our war behind us, and the public sentiment at the time, but later we regained that pride and understanding of what it meant to be a soldier and a combat veteran. To those Warriors who have fought and died, to the men we knew and lost, we will never forget you. To those who have served with honor and distinction hold fast to our motto – Having been lead by love of country. We salute you one and all.

Thank you.

Steve Ward, Bill Braniff, Arnold Krause, Craig Schoonderwoerd, 1LT Quinn Henson, who coordinated the event and acted as our laision officer.

Photos of the 2/12th command staff and the evenings events. Click on any photo to start slide show.

The dining-in is a formal dinner function for members of a military organization or unit. It

provides an occasion for cadets, officers, noncommissioned officers, and their guests to gather

together in an atmosphere of camaraderie, good fellowship, fun, and social rapport. It is

important to emphasize that a dining-in celebrates the unique bond or cohesion that has held

military units together in battle, rather then become just another mandatory function.

provides an occasion for cadets, officers, noncommissioned officers, and their guests to gather

together in an atmosphere of camaraderie, good fellowship, fun, and social rapport. It is

important to emphasize that a dining-in celebrates the unique bond or cohesion that has held

military units together in battle, rather then become just another mandatory function.

THE MILITARY DINING-IN

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

-24.jpg)

-26 LG.jpg)

-55.jpg)

-57.jpg)

-58.jpg)

-59.jpg)

-60.jpg)

-68.jpg)

-70.jpg)

-72.jpg)

-81.jpg)

-84.jpg)

-86.jpg)

-87.jpg)

-88.jpg)

-90.jpg)

-91.jpg)

-98.jpg)

-102.jpg)

-106.jpg)

-111.jpg)

-117.jpg)

-123.jpg)

-130.jpg)

-137.jpg)

-143.jpg)

-146.jpg)

-163.jpg)

-173.jpg)

-174.jpg)

-228.jpg)

-260.jpg)

-261.jpg)

-262.jpg)

-275.jpg)

-277.jpg)

-278.jpg)

-279.jpg)

-283.jpg)

-286.jpg)

-288.jpg)

-291.jpg)

-294.jpg)

-296.jpg)

-297.jpg)

-301.jpg)

-303.jpg)

-304.jpg)

-306.jpg)

-307.jpg)

-308.jpg)

-309.jpg)

-310.jpg)

-311.jpg)

-384.jpg)

-391.jpg)

-392.jpg)

-395.jpg)

-396.jpg)

-397.jpg)

-398.jpg)